Most of the time, eating is simple: you choose a food, you enjoy it, and your body breaks it down for fuel. But for many people struggling with digestive symptoms, chronic bloating, mysterious fatigue, or inflammatory flare-ups, food doesn’t always feel neutral or nourishing. It can feel unpredictable, sometimes even like the body sees certain foods as a threat.

That reaction often traces back to something surprisingly small yet powerful: the proteins inside the foods you eat.

Food proteins are the building blocks of nutrition. They’re essential for muscles, hormones, enzymes, and overall health. But in the wrong context, or when digestion is compromised, or when certain proteins resist breakdown, those same building blocks can activate the immune system in ways you might never expect. They can spark irritation in the gut lining, trigger immune surveillance pathways, raise inflammatory signals, and sometimes create a ripple effect that reaches far beyond the digestive tract.

This is where inflammation pathways come into focus. Understanding how food proteins interact with your gut and immune system can bring clarity to challenges you’ve been trying to decode for years.

This article will walk you through that landscape and what happens when food proteins enter the body, how the immune system evaluates them, why some proteins (including lectins) cause stronger reactions, and what you can do to support more resilience and less inflammation through everyday choices.

The Gut: Your First Line of Immune Defense

Before food proteins ever enter the bloodstream, they must pass through the gut, a complex, fortified environment built to extract nutrients while preventing harmful particles from slipping through. Nearly 70% of the body’s immune system sits in or around this region, constantly evaluating what passes by.

Your gut lining is made of a single layer of cells connected by tight junctions, forming an interface that lets digested nutrients in while keeping undigested particles, pathogens, and irritants out. Above that layer sit mucus, digestive enzymes, beneficial bacteria, and immune cells, each playing a role in assessing what “belongs” and what doesn’t.

Now enter food proteins.

Under ideal circumstances, proteins are broken down into smaller pieces, amino acids and short peptides, that are easy for the body to identify, absorb, and use. But not all proteins break down cleanly. Some resist digestion. Some bind to cell surfaces. Some interfere with protective barriers. And some trigger immune cells to stay on alert.

This is why food proteins are often the first molecules suspected when someone experiences immune activation or inflammation after eating. They are structurally complex, highly variable between foods, and capable of interacting with the body in ways carbohydrates and fats rarely do.

When Proteins Don’t Break Down Fully

Digestion is a finely tuned system, but it isn’t perfect and it doesn’t operate at the same level in every individual.

Several things can interfere with proper protein breakdown:

- Low stomach acid, which reduces the ability to denature proteins.

- Gut inflammation, which alters enzyme secretion and absorption.

- Stress, which slows digestion.

- Dysbiosis, where beneficial bacteria that support digestion are outnumbered by less helpful species.

- Specific proteins that naturally resist heat, acids, or enzymes.

When proteins arrive in the small intestine partially broken down, they can place more demand on the immune system.

Why does this matter?

Because the immune system is trained to evaluate unfamiliar or large protein fragments as potential hazards. If it cannot clearly identify a protein as safe, it may err on the side of caution and initiate a mild (or not-so-mild) inflammatory response.

This is not an allergy. Those involve IgE antibodies and can trigger immediate reactions. Instead, this is a lower-grade, chronic, innate-immune response that can manifest as:

- bloating

- fatigue

- joint stiffness

- skin irritation

- brain fog

- digestive discomfort

- changes in stool habits

It’s subtle enough to confuse people and persistent enough to become miserable over time.

Pattern Recognition: The Immune System’s Food Scanner

The immune system doesn’t see food the way you do. It looks for patterns.

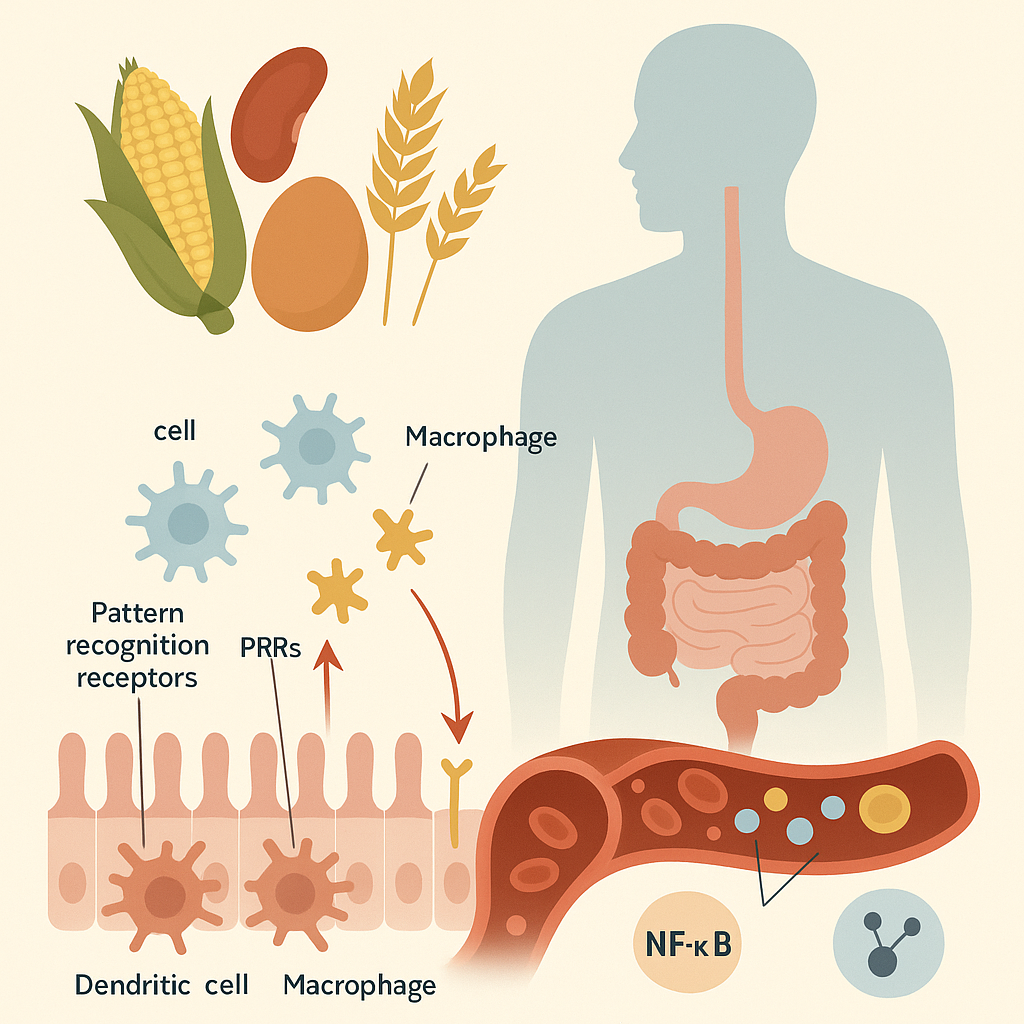

Immune cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and epithelial receptors monitor what enters the gut. They use pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including toll-like receptors (TLRs), to identify whether molecules appear friendly or dangerous.

When these receptors bind to an unfamiliar or irritating protein, they can activate inflammatory pathways such as:

- NF-κB, a master switch for inflammation

- Cytokines, chemical messengers like IL-6 or TNF-α

- Complement activation, a protein cascade often involved in defense

- Increased intestinal permeability, sometimes called “leaky gut”

If the same protein repeatedly triggers these alarms, the body becomes more sensitized over time. What may start as mild digestive irritation can gradually extend to systemic symptoms.

This is where diet becomes inseparable from immune health.

Lectins and Other Resistant Proteins

Lectins are one of the most discussed examples of “problematic proteins,” but they’re not the only players in this story.

Proteins that can affect the immune system include:

- Lectins (found in beans, grains, nightshades, certain nuts and seeds)

- Gluten proteins

- Prolamins, similar to gluten, in many grains

- Casein in dairy

- Protease inhibitors, naturally occurring in many plant foods

- Certain albumins in eggs or legumes

Among these, lectins stand out because they bind to carbohydrates on cell surfaces, especially in the gut. This binding action can:

- disrupt intestinal tight junctions

- interfere with nutrient absorption

- activate immune defense cells

- resist digestion

- survive cooking unless prepared properly

But it’s worth noting that not everyone reacts to all lectins or in the same way. Many lectins lose their problematic qualities when pressure-cooked, peeled, deseeded, or fermented.

The goal is not to demonize food but to understand how different proteins behave.

How Food Proteins Enter the Bloodstream and Why It Matters

For a protein to affect your immune system beyond the gut, it must cross the intestinal barrier.

Under normal conditions, this barrier is extremely selective. But several factors can loosen it:

- chronic inflammation

- alcohol

- stress hormones (like cortisol)

- dysbiosis

- certain medications

- high intake of irritating proteins

- nutrient deficiencies (zinc, vitamin D, omega-3s)

When the barrier becomes more permeable, partially digested proteins can slip into the bloodstream.

This is where immune activation tends to escalate.

Immune cells circulating throughout the body may interpret these proteins as foreign invaders. The liver becomes more burdened with inflammatory signals. Over time, this can contribute to systemic inflammation. Affecting joints, skin, brain function, and even mood.

People often describe this sensation as feeling “inflamed everywhere” without understanding the origin. In reality, their immune system may be responding to a constant flow of protein fragments it doesn’t recognize.

Inflammation: A Necessary Process That Can Become Overactive

Inflammation is not the enemy. It is one of the most powerful tools the body has for protecting itself. When used appropriately, it:

- destroys damaged cells

- signals for repairs

- recruits immune defense

- helps clear infections

But chronic inflammation is different. It’s inflammation without resolution, constant activation without adequate recovery.

Overactive responses to food proteins can contribute to this cycle. For example:

- a protein irritates the gut,

- the immune system responds,

- intestinal permeability increases,

- more protein fragments cross the barrier,

- the immune system escalates its response,

- the gut becomes even more inflamed.

This self-reinforcing loop is why dietary patterns matter so profoundly.

Not All Food Proteins Trigger Inflammation, Context Is Everything

It’s important to understand that proteins are not inherently harmful. The immune system does not react to all proteins equally. In fact, most proteins from well-prepared foods are welcomed and used for essential cellular functions.

The difference lies in:

- how the protein behaves structurally,

- how well your gut can break it down,

- the current condition of your digestive and immune systems, and

- how frequently you expose your body to that protein.

People with compromised digestion, chronic inflammation, or preexisting gut issues often react more strongly. Conversely, individuals with a resilient gut barrier may tolerate proteins that others cannot.

This is why dietary strategies must be personal, not universal.

How to Support Your Immune System Through Better Protein Handling

While you can’t change the structural properties of food proteins, you can improve how your body interacts with them.

Here are key approaches grounded in digestive physiology and immune science.

1. Strengthen Your Gut Barrier

A resilient barrier is the best defense against unnecessary immune activation. Helpful nutrients include:

- zinc, crucial for maintaining tight junction integrity

- omega-3 fatty acids, which lower inflammatory signaling

- vitamin D, which supports immune modulation

- collagen or gelatin, which provides amino acids used for gut lining repair

- polyphenol-rich foods, which reduce oxidative stress

2. Choose Preparation Techniques That Reduce Protein Irritation

Some proteins, especially lectins, can be dramatically altered by technique.

- Pressure cooking destroys lectins and many protease inhibitors.

- Fermentation breaks proteins down into simpler, more digestible peptides.

- Soaking and rinsing beans or grains reduces anti-nutrients.

- Peeling and deseeding nightshades removes lectin-rich structures.

These steps don’t eliminate nutrition. They often make foods more digestible and nutrient-rich.

3. Support Stomach Acid and Digestive Enzymes

Protein digestion begins in the stomach. Without adequate acidity or enzymatic support, large protein fragments can survive too long.

Small habits can improve digestive efficiency:

- not drinking excessive liquid during meals

- eating slowly and chewing thoroughly

- reducing stress before eating

- including bitter foods that stimulate digestive secretions

Digestive enzyme supplements are an option for some people but are not always necessary.

4. Identify Your Personal Protein Triggers

Not all individuals react to the same proteins. Keeping a food-symptom journal can reveal surprising patterns. Many people discover:

- specific beans cause issues, but others do not

- dairy proteins cause bloating but not digestive distress

- wheat proteins trigger fatigue more than gut symptoms

- nightshades affect joint pain

Understanding your patterns prevents unnecessary restriction.

The Bigger Picture: Inflammation Is Multifactorial

Even though food proteins are a major contributor to immune activation, they rarely act alone. Chronic inflammation often reflects a combination of factors:

- stress

- poor sleep

- environmental toxins

- viral load

- metabolic imbalance

- lack of movement

- overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria

Food, however, is the one factor you control every single day and often the most powerful lever for change.

When digestion is supported and protein interactions are minimized, the immune system becomes more balanced, more efficient, and less reactive. Many people report:

- better energy

- clearer thinking

- calmer digestion

- more stable mood

- improved sleep

- fewer aches

- better skin

These improvements are signs of inflammation pathways becoming quieter and more regulated.

Why Understanding Food Proteins Can Be Empowering

For many years, people were encouraged to believe that diet had little influence on inflammation unless a true allergy was present. But we now understand that the immune system reacts not only to pathogens but also to signals of irritation, molecular patterns, and chronic stressors, including those from food proteins.

Recognizing this shifts the conversation from “What’s wrong with my body?” to “What inputs am I giving my immune system each day?”

That simple shift, acknowledging the partnership between food and immune function, gives you more agency over your well-being.

You don’t need to fear food. You just need to understand how your unique biology responds to it, and how preparation, selection, and gut health shape that response.

Your immune system is not misbehaving; it is trying to protect you with the information it has. When you give it the right signals, nutrient-dense foods, reduced irritants, improved digestion, it recalibrates.

And when inflammation subsides, the body feels less like a battleground and more like a home you can live in comfortably again.

Final Thoughts

Food proteins are essential to life, yet they can become triggers for inflammation when digestion falters or when proteins resist breakdown. Their interactions with the gut and immune system create a dynamic landscape where small molecules can spark significant physiological changes.

But this isn’t a story about restriction. It’s a story about clarity, empowerment, and understanding the pathways that connect what you eat to how you feel.

By learning how food proteins interact with inflammation pathways, you gain insight into:

- why certain foods feel calming while others feel disruptive

- how to prepare foods to reduce irritation

- how to strengthen your gut barrier

- how to support a more balanced immune response

This is the foundation for long-term dietary peace: not perfection, not rigidity, just an informed partnership between your body and the foods that nourish it.