For anyone who has ever gone down the rabbit hole of gut health, the term lectins tends to appear with an almost mythical aura that is spoken of as invisible saboteurs hiding in ordinary foods, capable of wreaking havoc on the digestive lining. For others, lectins are merely plant proteins doing what plant proteins do, unfairly villainized by oversimplified online discussions. And somewhere between these poles sits the actual science, which is far more nuanced than either camp tends to admit.

Over the last decade, research into gut permeability, often called “leaky gut”, has expanded rapidly. Scientists are now far more aware of how the intestinal barrier reacts to stressors, diet, immune triggers, and microbial metabolites. Alongside this, interest in dietary lectins has grown as researchers attempt to understand whether these proteins meaningfully influence barrier integrity in humans. While the conversation is still evolving, current research offers several compelling insights about how lectins interact with the gut lining, when they may cause harm, and why some people respond so differently from others.

This article weaves through the emerging science, not just what the studies show, but how researchers think about the gut as a living, reactive environment, and the kinds of mechanisms they’re trying to unravel.

The Gut Barrier: A Living Organ With Rules of Engagement

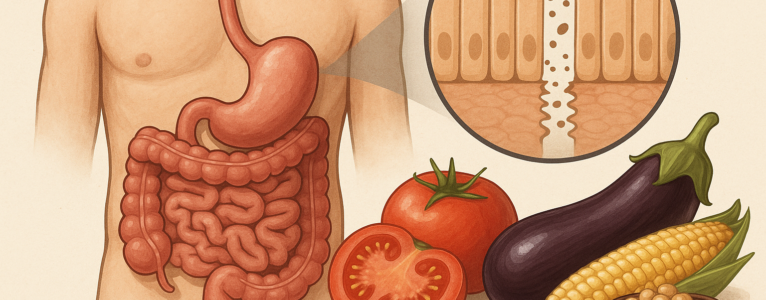

One of the most important shifts in digestive health science is the understanding that the gut isn’t a simple pipe for food; it’s a dynamic ecosystem that negotiates with everything that enters. The intestinal lining works like a selective gatekeeper, allowing nutrients to pass through while blocking pathogens, allergens, and potentially harmful molecules. This gatekeeping function depends heavily on tight junctions, microscopic structures that weld one intestinal cell to the next.

When tight junctions loosen, permeability increases. Under the microscope, this looks like small openings between cells. But on a practical level, it means substances that normally remain in the digestive tract like food fragments, bacterial components, and inflammatory molecules, gain a direct route into the bloodstream. This can activate immune responses, amplify inflammation, or in susceptible individuals, contribute to digestive symptoms.

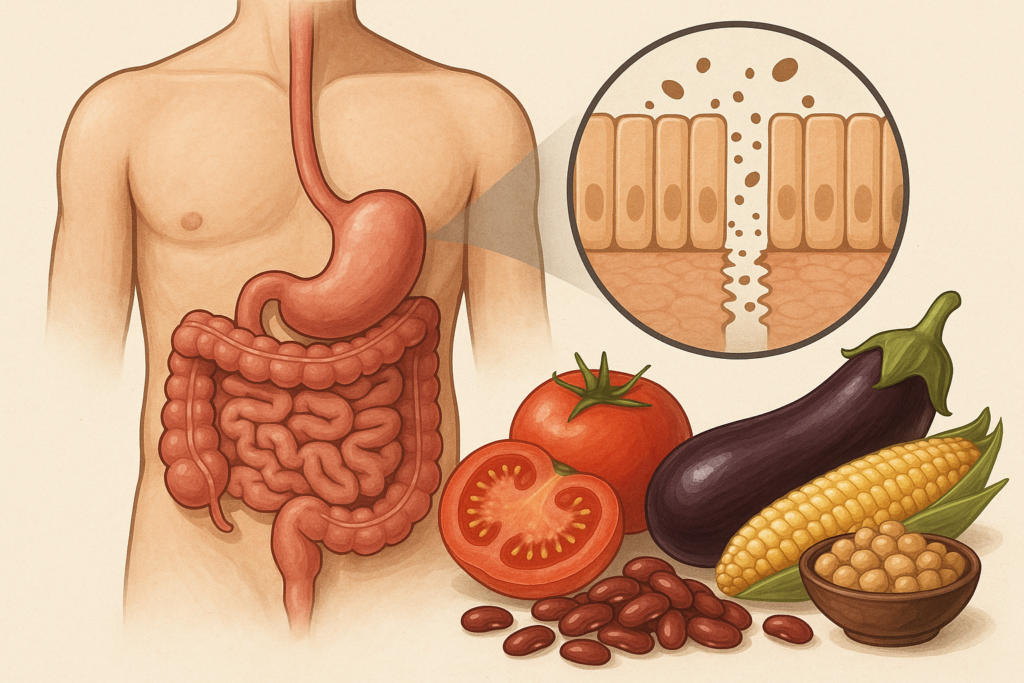

Lectins enter this story because several well-studied lectins (including phytohemagglutinin from beans, wheat germ agglutinin from wheat, and certain lectins from nightshades) have demonstrated the ability in test systems to bind to intestinal cells. The question becomes: Does this binding matter in real human digestion? Does it loosen tight junctions? Does it provoke immune reactions? Researchers have been trying to parse this out, and while not all answers are final, the patterns are becoming clearer.

What Lectins Actually Do in the Gut According to Controlled Studies

Lectins are naturally occurring proteins that plants use for defense. Their stickiness and their affinity to bind sugars on cell surfaces is exactly why they are biologically active in the digestive tract. In vitro research (meaning studies in test tubes or on isolated cell lines) consistently shows that lectins bind to intestinal epithelial cells. This binding can trigger a few possible reactions:

- Interference with nutrient absorption

- Changes in cellular signaling pathways

- Alteration of tight junction proteins

- Stimulation of immune cell activity

But the leap from in vitro to human digestion is not a short one. In actual food preparation, lectins are exposed to heat, moisture, pH changes, enzymes, microbial competitors, and digestive processes that often neutralize or degrade them. For example, studies on phytohemagglutinin, a famously potent lectin in raw kidney beans, show dramatic toxicity only when beans are undercooked. Proper boiling destroys the lectin almost entirely.

Still, some lectins, particularly wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), resist digestion more than others. Research published in journals like Nutrients, Frontiers in Immunology, and Gut has explored how WGA can interact with intestinal cells even after cooking and digestion. In several cell-line experiments, WGA increased permeability by altering proteins such as zonulin, claudin, or occludin, molecules crucial for maintaining tight junction integrity.

Yet the biggest question remains:

Does this happen inside an actual human gut, not just a dish of isolated cells?

The Zonulin Connection: Where Lectins and Permeability Meet

One of the most influential developments in gut permeability research is the discovery of zonulin, a protein that modulates tight junctions. Zonulin acts like a dimmer switch for permeability, increasing the openness of the intestinal gate when activated. The most well-documented trigger for zonulin release is gliadin, the lectin-like component of gluten.

Multiple studies, including research led by Dr. Alessio Fasano at Harvard, have demonstrated that gliadin can induce zonulin release in both celiac and non-celiac individuals. This doesn’t mean that gluten harms everyone, but it does suggest that lectin-like proteins can influence permeability through signaling pathways, especially in people with a predisposed immune response.

Researchers are now exploring whether other lectins, beyond gliadin, may stimulate zonulin or similar pathways. Evidence is still mixed. Some lectins show activity in vitro, others show no measurable effect in human feeding studies. But this scientific interest highlights a pattern: the gut responds not only to chemical irritants but also to proteins that interact with cell receptors.

In other words, lectins don’t have to physically damage the gut to influence permeability. They can do so through biochemical conversations with the gut lining.

Animal Studies: A Cautionary but Useful Lens

Because human trials are expensive, slow, and ethically limited, many early studies on lectins and the gut rely on rodent models. These experiments often show dramatic results: rodents fed high-lectin diets develop intestinal abnormalities, immune activation, or altered gut morphology.

But these findings come with three major caveats:

- Rodents are more sensitive to lectins than humans.

- Doses used in studies often far exceed typical human intake.

- Lectins are often administered isolated or raw, not as part of cooked foods.

That said, animal studies remain important because they reveal possible mechanisms, how lectins might affect the intestinal barrier under certain conditions. Studies in pigs, for instance, have shown increased permeability when fed raw legume lectins. Similar studies in rats showed villi damage from undercooked red kidney bean lectins.

Researchers generally agree on one takeaway:

Most harmful effects appear when lectins are consumed in their unprocessed, concentrated, or improperly cooked forms.

This echoes traditional cooking practices around the world like soaking, fermenting, sprouting, and pressure cooking, which appear in modern research not as folk superstition but as biochemically meaningful methods of lectin reduction.

Human Studies: Where the Story Gets Messy

When researchers shift from petri dishes and rodents to living humans, the landscape becomes more complicated. People differ dramatically in genetics, microbiome composition, existing gut health, digestive enzyme output, and immune responsiveness. The same lectin that irritates one individual may be entirely tolerated by another.

What current human studies suggest:

1. Lectins can influence permeability in susceptible individuals.

Those with inflammatory bowel conditions, celiac disease, autoimmune disorders, or pre-existing permeability may respond more strongly to lectins such as WGA or certain legume lectins.

2. Healthy individuals often experience no measurable effect.

In people with robust gut integrity and a balanced microbiome, lectins from properly prepared foods tend to pass without incident.

3. Cooking dramatically reduces problematic lectin activity.

Pressure cooking, boiling, fermenting, and sprouting decrease lectin content to levels that most individuals tolerate well.

4. The microbiome plays a surprisingly large role.

Emerging studies show that certain microbes can degrade or neutralize lectins. A diverse microbiome may therefore act as a buffer, reducing potential lectin-induced irritation.

Human research is far from complete, but its direction suggests that lectins and permeability must be understood within the context of the individual gut ecosystem, not merely the foods alone.

Where Scientific Debate Still Exists

Some researchers argue that lectin-related gut permeability has been overstated in popular health writing. They point out that most studies showing strong lectin effects use concentrations totally unrealistic in everyday diets. Critics also note that many foods richest in lectins like beans, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains correlate in large epidemiological studies with longevity and reduced chronic disease risk.

Others counter that population-level studies may hide individual sensitivities, especially in people with autoimmune tendencies or microbiome imbalances. For such individuals, even small disruptions in barrier function may matter, and lectins might be one of several dietary contributors to a sensitive or reactive gut.

This debate is actually a sign of a healthy scientific environment. As research progresses, the field is moving away from overly simplistic narratives of “lectins are universally dangerous” or “lectins are harmless to everyone” and moving toward more personalized interpretations.

The Emerging Consensus: Lectins Aren’t One-Size-Fits-All

Although lectin science is ongoing, several themes have become increasingly accepted:

1. The gut barrier is more dynamic than once believed. Permeability increases naturally during vigorous exercise, stress, infection, alcohol intake, and exposure to certain food components, including lectin-like proteins.

2. Lectins can influence permeability, but context matters. Dose, preparation method, microbial balance, and individual genetics all modify the outcome.

3. Some lectins are considerably more resilient than others. Wheat germ agglutinin and certain legume lectins draw the most research interest because they resist digestion and bind strongly to intestinal cells.

4. Removing lectins often improves symptoms in sensitive individuals. People with autoimmune conditions, IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, or post-infectious gut dysfunction frequently report improvements when reducing lectin-heavy foods, particularly grains, nightshades, and improperly prepared legumes.

5. Traditional food preparation speaks to an ancient understanding. Pressure cooking, fermenting, sprouting, and soaking have modern biochemical support as methods that reduce lectin activity and improve digestibility. This alignment between ancestral cooking and scientific evidence is one of the most intriguing developments in the field.

A Future Direction: Personalized Gut Nutrition

Where research seems to be heading isn’t toward a universal dietary rule but toward precision nutrition. The next decade will likely bring tools that assess permeability, microbiome lectin-metabolizing capacity, inflammatory markers, and food sensitivity with far more accuracy than today’s tests.

In that future landscape, lectins won’t be labeled simply as villains or non-issues. They’ll be seen as part of a broader conversation between food molecules and the gut ecosystem. Some bodies will negotiate with lectins peacefully. Others may require boundaries or preparation techniques to maintain harmony.

For now, the best interpretation of current research is this:

- Lectins can affect gut permeability through biochemical signaling or binding interactions.

- Their impact depends heavily on the individual.

- The gut heals best when supported by careful preparation, diverse microbes, adequate sleep, stress reduction, and nutrient-rich whole foods.

- Lectins are neither universally harmful nor universally harmless. They are biologically active plant proteins with context-dependent effects.

In Closing: What the Science Truly Suggests

The story of lectins and gut permeability mirrors a larger truth about health science. The body is not governed by a single villainous molecule or magic ingredient. Instead, it’s shaped by interplay between diet, microbiome, immune response, lifestyle, and genetics. Lectins participate in this interplay in meaningful ways, but rarely alone.

What we’re learning is not to fear lectins blindly, but to understand them within the biology of your own digestion. For many, they are benign. For some, they are irritants. For others still, they are manageable with proper cooking or occasional avoidance.

Current research, while ongoing, consistently points to this balanced view:

lectins interact with the gut barrier, but your response depends on the story your gut is already telling.

And the more we understand that story through science, personal experience, and thoughtful experimentation, the clearer and more individualized our dietary choices can become.