The human gut microbiome is one of the most complex ecosystems on the planet. Trillions of microorganisms coexist within the digestive tract, forming a dynamic community that influences digestion, immunity, metabolism, and even mood and cognition. What we eat shapes this ecosystem profoundly, not only through macronutrients like fiber and fat, but also through bioactive compounds that interact directly with microbes and the intestinal lining.

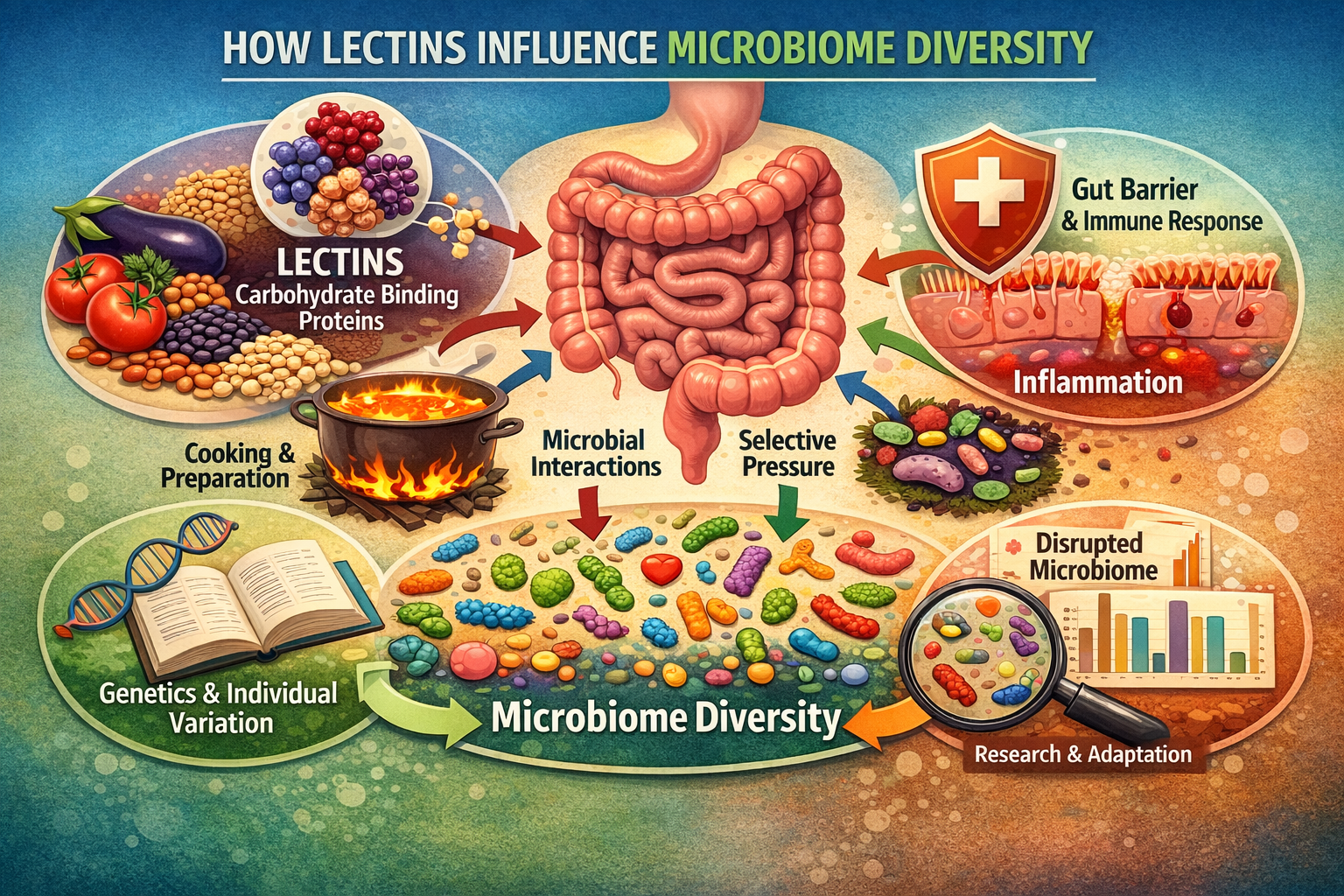

Among these compounds, lectins occupy a particularly controversial space. Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins found throughout the plant kingdom, especially in legumes, grains, seeds, and certain vegetables. Some researchers view them as benign or even beneficial under normal dietary conditions. Others raise concerns about their potential to disrupt gut integrity and alter microbial balance. Understanding how lectins influence microbiome diversity requires moving beyond simplistic labels and examining the nuanced ways these proteins interact with both microbes and host tissues.

This article explores what lectins are, how they interact with the gut environment, and what current research suggests about their role in shaping microbiome diversity.

The Microbiome as a Living Ecosystem

Microbiome diversity refers to both the number of microbial species present and the balance between them. A diverse microbiome is generally associated with resilience, meaning it can adapt to stressors such as dietary change, illness, or medication. Reduced diversity, by contrast, is often observed in conditions involving chronic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and immune dysregulation.

Microbial diversity is influenced by many factors, including genetics, early-life exposures, antibiotic use, stress, sleep, and diet. Food provides not only energy for microbes but also structural signals that affect where they colonize and how they interact with one another. Some dietary compounds act as selective pressures, favoring the growth of certain microbes while inhibiting others. Lectins are one such compound.

What Lectins Are and Why Plants Produce Them

Lectins are proteins that bind to specific carbohydrate structures. In plants, they serve primarily as defense molecules. By attaching to sugars on the surfaces of insects, fungi, or herbivores’ gut cells, lectins can interfere with digestion or nutrient absorption, discouraging consumption.

In humans, dietary lectins are not completely broken down during digestion. Many resist stomach acid and digestive enzymes, allowing them to reach the small intestine in an intact or partially intact form. Their carbohydrate-binding properties remain active, which means they can interact with sugars on intestinal cells and microbial surfaces alike.

This dual ability to bind both host and microbial carbohydrates is central to how lectins may influence microbiome composition.

Lectins and the Intestinal Surface

The gut lining is coated with a layer of mucus rich in glycoproteins. These sugar-containing molecules help protect epithelial cells and provide attachment sites for beneficial microbes. Certain gut bacteria specialize in binding to and metabolizing these mucus-derived sugars, forming a close relationship with the host.

Lectins that survive digestion can bind to similar carbohydrate structures within this mucus layer. Depending on the lectin type and concentration, this binding may alter mucus structure, interfere with microbial attachment, or stimulate immune signaling in the underlying tissue. Changes in the intestinal surface environment can ripple outward, influencing which microbes thrive and which decline.

Direct Interactions Between Lectins and Gut Microbes

Microbes themselves are coated in complex carbohydrates. Bacterial cell walls, capsules, and surface proteins often contain sugars that lectins can recognize and bind. When lectins attach directly to microbes, several outcomes are possible.

In some cases, binding may inhibit microbial growth by interfering with nutrient uptake or cell division. In other cases, lectins may promote microbial aggregation, causing certain species to cluster together or adhere more strongly to intestinal surfaces. These effects can selectively favor or suppress specific microbial populations, thereby shaping overall diversity.

Importantly, not all microbes respond to lectins in the same way. Sensitivity varies widely depending on species, strain, and environmental context.

Selective Pressure and Microbiome Shifts

Microbiome diversity is not only about how many species exist, but also about which species dominate. Lectins can act as selective pressures by creating an environment that advantages lectin-resistant microbes.

Some gut bacteria have evolved mechanisms to degrade or tolerate lectins. These microbes may gain a competitive edge in diets rich in lectin-containing foods. Over time, this can shift microbial balance toward species that are better adapted to lectin exposure, potentially reducing the presence of more sensitive strains.

Whether this shift is beneficial or harmful depends on the functional roles of the microbes involved. Diversity alone does not guarantee health; composition and metabolic output matter just as much.

Lectins, Inflammation, and Microbial Balance

The immune system is tightly intertwined with the microbiome. Intestinal immune cells constantly monitor microbial populations and respond to perceived threats. Lectins can influence this relationship indirectly by stimulating immune signaling.

Some lectins have been shown in experimental models to increase intestinal permeability or activate inflammatory pathways when consumed in high amounts or under certain conditions. Inflammation alters the gut environment by changing oxygen levels, nutrient availability, and antimicrobial peptide secretion. These changes often reduce microbial diversity and favor inflammation-tolerant species.

In this way, lectins may influence microbiome diversity not by acting directly on microbes, but by modifying the immune landscape in which microbes exist.

Cooking, Processing, and Lectin Activity

One critical factor often overlooked in discussions of lectins is food preparation. Many lectins are heat-sensitive and are significantly reduced or deactivated through proper cooking methods such as boiling, soaking, fermenting, or pressure cooking.

When lectin activity is reduced, their ability to bind carbohydrates and interact with microbes diminishes accordingly. This means that the microbiome effects of lectins can vary dramatically depending on how foods are prepared.

Populations that traditionally consume lectin-rich foods often use preparation techniques that mitigate lectin activity. These cultural practices may help explain why lectins do not produce uniform effects across different dietary patterns.

Individual Variation in Microbiome Response

No two microbiomes are identical. Genetics, early microbial exposure, and long-term dietary habits all influence how an individual responds to lectins. A microbiome already adapted to plant-rich diets may handle lectins differently than one shaped by highly processed foods.

Some individuals may experience minimal microbiome disruption, while others may see noticeable changes in microbial composition or digestive comfort. These differences highlight the importance of personalization when evaluating lectins and microbiome health.

Potential Benefits and Adaptive Responses

It is important to note that not all lectin-microbiome interactions are necessarily negative. Mild selective pressures can encourage microbial adaptation and resilience. Some researchers hypothesize that low-level lectin exposure may promote microbial diversity by preventing overgrowth of dominant species, similar to how ecological disturbances can sometimes increase biodiversity.

Additionally, lectins may act as signaling molecules, influencing microbial gene expression or metabolic activity in ways that are still being explored. The microbiome is highly adaptable, and not all shifts represent dysfunction.

Current Research Limitations

Much of what we know about lectins and the microbiome comes from animal studies, cell culture experiments, or short-term human trials. Translating these findings into long-term human outcomes remains challenging.

Dietary patterns involve countless interacting variables, making it difficult to isolate the effects of lectins alone. Fiber content, polyphenols, fats, and food processing methods all influence microbiome diversity and can confound results.

As research advances, more sophisticated tools such as metagenomics and metabolomics are helping clarify how lectins influence microbial ecosystems in real-world settings.

Practical Implications for Microbiome Health

From a practical standpoint, the relationship between lectins and microbiome diversity suggests moderation and context matter more than blanket avoidance. Supporting microbiome health involves a combination of dietary diversity, proper food preparation, and attention to individual tolerance.

Focusing on whole foods prepared using traditional methods, supporting gut integrity through adequate nutrition, and observing personal responses can help individuals navigate lectin intake without unnecessary restriction.

Conclusion

Lectins influence microbiome diversity through a web of direct and indirect mechanisms. By binding to carbohydrates on microbes and intestinal tissues, they can shape microbial attachment, growth, and competition. Through immune modulation and effects on gut barrier function, they can further alter the ecological landscape of the gut.

These influences are not universally harmful or beneficial. They depend on lectin type, dose, food preparation, microbiome composition, and individual physiology. As research continues to evolve, it is becoming clear that lectins are not simple villains or heroes, but active participants in the complex dialogue between diet, microbes, and human biology.

Understanding this nuanced relationship allows for more informed dietary choices and a deeper appreciation of how even small proteins can shape one of the most important ecosystems in the human body.