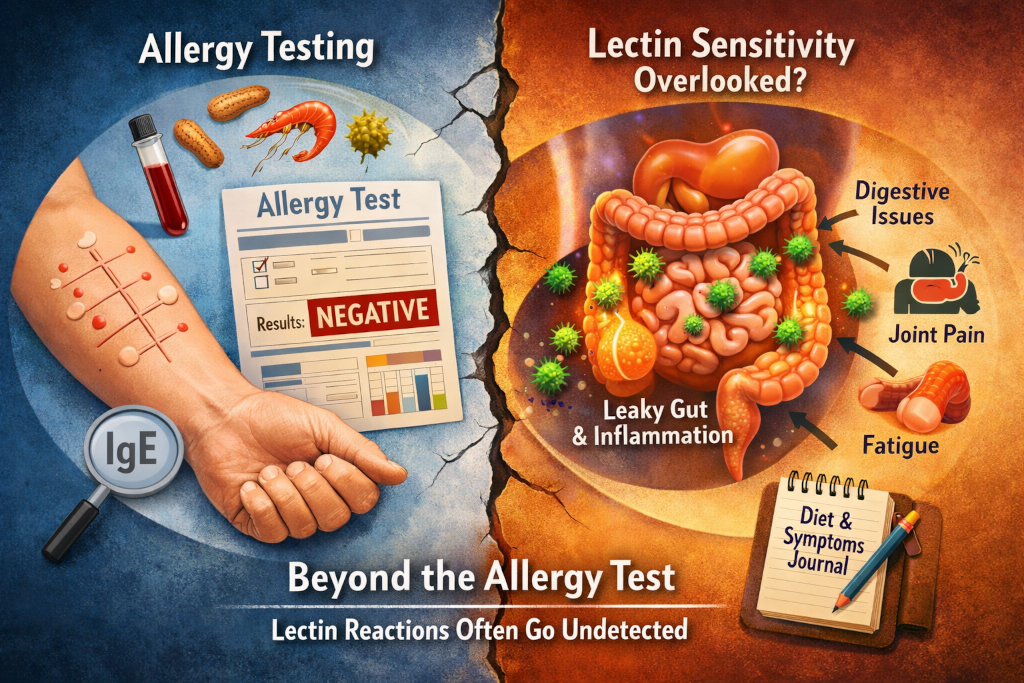

For many people beginning a low-lectin journey, the first instinct is to seek confirmation. If food is causing symptoms, there must be a test that can identify the culprit. Modern medicine has trained us to look for neat answers in lab results, preferably in black-and-white numbers that validate our lived experience. Yet when it comes to lectins, this expectation often leads to frustration. People suspect a food is causing inflammation, digestive distress, joint pain, or neurological symptoms, but standard allergy tests come back negative. The conclusion feels obvious and discouraging: If the test says I am not allergic, then lectins must not be the problem.

This disconnect is not a failure of intuition or an imagined sensitivity. It reflects a deeper issue rooted in how allergy testing works and how lectins interact with the body. Lectins do not behave like classic allergens, and the immune system does not always treat them the same way it treats pollen, peanuts, or shellfish. To understand why lectins often evade detection, we need to explore how allergy tests are designed, what they measure, and what lectins actually do once they enter the body.

What Allergy Tests Are Designed to Detect

Conventional food allergy testing focuses on a specific immune response pathway. Skin prick tests and blood tests typically measure immunoglobulin E, or IgE. This antibody is involved in immediate allergic reactions. When someone with an IgE-mediated allergy eats a triggering food, the immune system reacts quickly. Histamine is released, and symptoms such as hives, swelling, itching, wheezing, or even anaphylaxis may occur within minutes.

These tests are extremely useful for identifying life-threatening allergies. They are designed to answer one narrow question: Does this food provoke an immediate IgE-mediated immune response? If the answer is yes, the test is positive. If the answer is no, the test is negative.

Lectins rarely trigger this pathway.

Lectins are proteins, but they are not allergens in the classic sense. They do not typically cause sudden histamine release or dramatic, immediate reactions. Instead, their effects are often slower, cumulative, and more subtle. They interact with the gut lining, immune cells, and sometimes nerve tissue in ways that unfold over hours, days, or even weeks. Because IgE tests are not designed to detect this kind of interaction, lectins often pass under the radar.

Lectins and the Immune System Speak a Different Language

The immune system is not a single switch that turns on or off. It is a complex communication network with multiple signaling pathways, feedback loops, and regulatory mechanisms. IgE is just one small part of that system.

Lectins tend to interact with immune pathways that are not measured in standard allergy testing. Many lectins bind to carbohydrates on the surface of cells, including cells lining the gut and cells involved in immune regulation. This binding can influence how tightly the intestinal barrier is held together, how immune cells interpret what is “foreign,” and how inflammatory signals are amplified or dampened.

Instead of causing an acute allergic reaction, lectins may contribute to low-grade, chronic immune activation. This can look like persistent inflammation, immune confusion, or exaggerated responses to other stressors. These patterns are often associated with IgG antibodies, innate immune responses, or inflammatory cytokines rather than IgE. Most routine allergy tests do not measure these factors in a clinically meaningful way.

This is why someone can eat a food containing lectins, feel unwell for days afterward, and still test “negative” for food allergies. The immune system is responding, but not in the way the test is built to detect.

The Gut Barrier Is Central to the Story

One of the most important reasons lectins escape allergy tests lies in their relationship with the gut lining. The intestinal barrier is not just a passive tube. It is an active, intelligent interface between the outside world and the immune system. Its job is to allow nutrients through while keeping larger, potentially harmful molecules out.

Certain lectins are known to bind to the cells of the intestinal lining and interfere with this barrier function. When this happens, permeability can increase. This does not necessarily cause immediate pain or visible damage, but it can allow substances to pass through that normally would not. The immune system may then respond to these substances rather than to the lectin itself.

In this scenario, lectins act less like a direct trigger and more like a facilitator. They set the stage for immune dysregulation without being the star of the show. Allergy tests are not designed to detect this kind of indirect influence. They look for antibodies against specific foods, not for subtle changes in gut permeability or immune tolerance.

Delayed and Cumulative Effects Are Hard to Capture

Another challenge with lectins is timing. Classic food allergies follow a predictable timeline. Exposure leads to symptoms quickly, often within minutes. Lectin reactions are frequently delayed. Symptoms may appear hours later or the next day, and they may build gradually with repeated exposure.

This delay makes lectin sensitivity difficult to correlate with a single food or meal. By the time symptoms appear, the triggering food may be long gone from the digestive tract. Allergy tests, which rely on immediate immune recognition, are poorly suited to identify triggers with delayed effects.

Cumulative exposure further complicates the picture. A single serving of a lectin-containing food may not cause noticeable symptoms, but repeated consumption over time may cross a threshold. The immune system may become progressively more reactive, or the gut barrier may become increasingly compromised. Allergy tests capture a snapshot in time, not the long-term dynamics of exposure and response.

Why Negative Tests Can Be Misleading

When people receive negative allergy test results, they are often told that food is not the problem. This can lead to self-doubt, dismissal of symptoms, or the assumption that discomfort is purely psychological. For those dealing with lectin sensitivity, this message can be particularly damaging.

A negative allergy test does not mean that a food has no effect on the body. It simply means that the effect does not fit the narrow criteria the test was designed to measure. Lectin-related issues exist in a gray area between allergy, intolerance, and immune modulation. Modern medicine is still catching up to this complexity.

This gap explains why many people only discover lectin sensitivity through careful observation, elimination, and reintroduction rather than through laboratory confirmation. The body becomes the primary source of data, and symptoms become meaningful signals rather than inconveniences to be ignored.

The Role of Individual Variability

Not everyone reacts to lectins in the same way. Genetics, gut microbiome composition, stress levels, sleep quality, and overall immune health all influence how the body responds. Some people can eat lectin-rich foods daily with no apparent issues. Others experience significant symptoms from relatively small amounts.

This variability further limits the usefulness of standardized testing. Allergy tests assume a consistent, reproducible immune response across individuals. Lectin sensitivity does not follow that pattern. It is shaped by context, history, and cumulative exposure. Two people can eat the same food and have entirely different outcomes, neither of which will necessarily show up on a test panel.

A Different Kind of Evidence

Because lectins often evade traditional testing, evidence of their impact tends to emerge through patterns rather than single data points. People notice improvements when certain foods are prepared differently, fermented, pressure cooked, or removed entirely. Symptoms may improve alongside changes in sleep, digestion, or inflammatory markers rather than disappearing overnight.

This experiential evidence is not less valid simply because it is harder to measure. In many areas of nutrition and immune health, subjective experience has historically preceded scientific explanation. Lectins occupy a similar space. Research continues to evolve, but lived experience has already revealed important truths about how these proteins interact with the body.

Rethinking What “Testing” Means

The absence of a definitive lectin test does not mean lectins are irrelevant. It means our testing tools are still limited. As science advances, new methods may emerge that better capture immune modulation, gut barrier integrity, and chronic inflammatory patterns. Until then, understanding lectins requires a broader definition of evidence.

This includes symptom tracking, dietary experiments, and an appreciation for how the immune system communicates beyond immediate allergic reactions. It also requires humility. Not every biological interaction fits neatly into existing diagnostic categories, and lectins are a clear example of that reality.

Listening Beyond the Lab Results

For people navigating unexplained symptoms, negative allergy tests can feel like a dead end. In the context of lectins, they are better understood as incomplete information rather than a final answer. The body’s responses, when observed carefully and consistently, often tell a more nuanced story.

Lectins remind us that health is not always binary. Reactions are not always loud, immediate, or easily classified. Sometimes they unfold quietly, influencing systems over time rather than announcing themselves in dramatic fashion. Recognizing this helps explain why lectins are not always detectable through allergy tests and why so many people find clarity only when they look beyond them.

In the end, the goal is not to reject testing but to understand its limits. When those limits are acknowledged, lectins make much more sense, and so do the experiences of the people affected by them.