One of the quiet assumptions most people make about food is that once it is cooked, it is “done.” The cooking step is treated as a finish line. Food goes from raw to safe, from dangerous to edible, from problematic to resolved. Yet anyone who has lived with digestive sensitivity for long enough knows that food does not always behave so neatly. Leftovers that felt fine the first night can suddenly cause discomfort the next day. A meal that was well tolerated fresh might feel heavier, foggier, or more inflammatory when reheated. These experiences are often brushed off as coincidence, but there are real biochemical reasons they happen.

Lectins sit at the center of this mystery.

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins found throughout the plant kingdom. Plants evolved them as defense tools. They help plants deter insects, resist microbes, and survive being eaten. When humans consume lectins, most people tolerate them without issue. Others, however, experience digestive symptoms, inflammation, joint discomfort, or immune activation. The low-lectin framework is not about fear of plants.

It is about understanding how preparation, processing, and repetition change the way plant proteins interact with the human body. Reheating food is one of the least discussed but most important variables in that equation.

Cooking Does Not End the Story

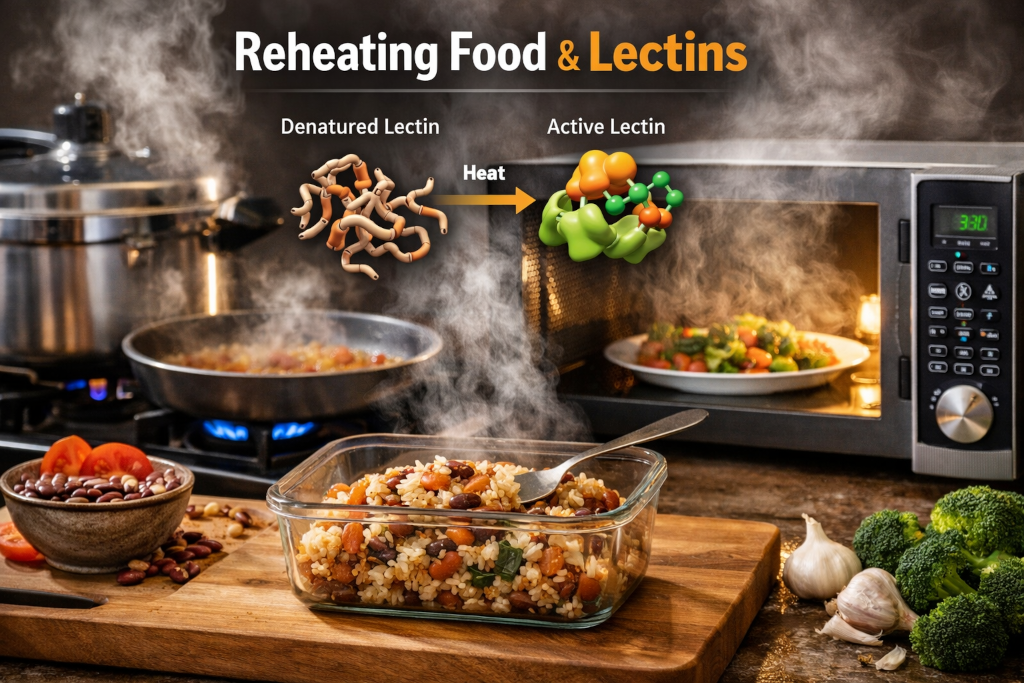

To understand reheating, it helps to first understand what cooking actually does to lectins. Lectins are proteins, and proteins have shape. That shape determines how they behave in the body. Heat alters that shape. When heat is sufficient, lectins lose their ability to bind to carbohydrates in the gut lining. This is why methods like pressure cooking, long boiling, and fermentation dramatically reduce lectin activity.

But heat does not destroy all proteins permanently. Some proteins unfold under heat, then refold as they cool. Others partially denature and settle into new configurations. Cooling, storage, and reheating introduce time and temperature shifts that can change protein behavior again.

This does not mean reheating “brings lectins back to life” in a simple sense. It means that lectin activity is dynamic rather than binary. Instead of thinking in terms of on or off, it is more accurate to think in terms of reduced, altered, or redistributed activity.

Cooling Changes Structure, Not Just Temperature

When cooked food cools, especially starchy plant foods, its internal structure changes. This is most often discussed in the context of resistant starch, where cooling cooked starches allows some carbohydrates to reorganize into forms that resist digestion. Less often discussed is that proteins are undergoing changes at the same time.

Lectins that were loosened or partially denatured by heat can interact differently with surrounding carbohydrates as food cools. In some cases, they may become less accessible to digestive enzymes. In others, they may bind to newly structured carbohydrates in ways that slow digestion or alter gut signaling.

For people with resilient digestion, these shifts are irrelevant. For people already sensitive to lectins, histamines, or fermentable fibers, the changes can be noticeable. This is why someone might tolerate freshly cooked lentils but feel bloated after eating them reheated the next day, even if the portion size is identical.

Reheating Is Not the Same as Cooking

Reheating food does not replicate the original cooking process. Most reheating methods apply uneven heat, shorter duration, and lower overall temperatures. A microwave, for example, excites water molecules but does not maintain uniform protein-denaturing heat throughout the food. A quick stovetop reheat may warm the surface while leaving the interior relatively unchanged.

This matters because lectin reduction depends on sustained heat exposure. If a food was marginally cooked the first time, reheating may not deepen lectin reduction. Instead, it may simply warm a food whose protein structure has already stabilized into a new form during cooling. In practical terms, this means reheating does not always make food “safer” from a lectin standpoint. In some cases, it can make digestion more challenging.

The Role of Storage Time

Time is an often overlooked factor in lectin response. The longer cooked food sits, the more opportunity there is for chemical rearrangement, moisture migration, and microbial interaction. Even under refrigeration, enzymes remain active at low levels. Proteins continue to interact with carbohydrates, fats, and minerals. This does not mean leftovers are unsafe or unhealthy. It means they are not chemically identical to the meal you ate the night before.

Some people notice no difference whether food is eaten immediately or three days later. Others consistently report symptoms emerging on day two or three. When lectins are part of the picture, this pattern makes sense. The gut is responding not just to what the food contains, but how those compounds present themselves at the moment of digestion.

Why Pressure-Cooked Foods Behave Differently

Pressure cooking deserves special mention because it changes the reheating equation entirely. Pressure cooking exposes food to temperatures higher than standard boiling, long enough to significantly disrupt lectin structure. This deeper denaturation makes lectins less likely to refold into active shapes during cooling.

As a result, pressure-cooked foods tend to reheat more predictably. This is one reason many people following a low-lectin approach rely heavily on pressure cooking for batch meals. The initial reduction is strong enough that reheating does not meaningfully increase lectin activity.

By contrast, foods that were lightly sautéed, steamed, or baked may not have reached sufficient temperatures to fully destabilize lectins in the first place. Cooling and reheating these foods may simply cycle them through structural shifts without ever fully neutralizing lectin activity.

Individual Tolerance Still Matters

No discussion of lectins is complete without acknowledging individual variation. The same reheated meal can be harmless for one person and problematic for another. Gut integrity, enzyme production, microbiome balance, immune sensitivity, and overall inflammatory load all influence how lectins are handled.

This is why lectins should never be framed as universally harmful or universally irrelevant. They are context-dependent compounds. Reheating changes that context in subtle but real ways. For someone early in their low-lectin journey, reheated foods may provoke symptoms simply because their digestive system is still reactive. As gut health improves, tolerance often increases. Many people find that foods they once had to eat fresh can later be reheated without issue.

The Psychological Trap of “It Worked Before”

One of the most frustrating aspects of lectin sensitivity is delayed feedback. A food that worked yesterday may not work today, even when it is technically the same meal. This leads to confusion and self-doubt. People assume they are imagining patterns or overthinking their symptoms.

Understanding reheating removes much of that confusion. The body is responding to real biochemical differences, not personal inconsistency. The meal is similar, but it is not identical. This realization can be empowering. Instead of abandoning entire food groups, people can adjust preparation methods, storage duration, and reheating techniques to improve tolerance.

Reheating Techniques Can Make a Difference

Although reheating cannot undo structural changes that occur during cooling, it can influence how food is digested. Longer reheating at gentler temperatures tends to be better tolerated than rapid, uneven heating. Adding moisture during reheating can help proteins relax rather than tighten.

Thorough reheating, rather than lukewarm warming, may improve enzyme access in the gut. These are not rigid rules but patterns observed by many people experimenting thoughtfully with their diets.

Lectins Are Not the Only Factor, But They Matter

It is important to state clearly that reheated food issues are not caused by lectins alone. Histamine accumulation, bacterial byproducts, and changes in fat oxidation also play roles. However, lectins are one of the few components that directly interact with gut lining receptors, immune signaling pathways, and carbohydrate digestion.

When lectin activity changes, the gut feels it quickly. Understanding this does not require a biochemistry degree. It requires noticing patterns, respecting preparation methods, and giving the body credit for responding intelligently to its environment.

A More Flexible Way Forward

The goal of low-lectin living has never been perfection. It is awareness. Reheating food does not automatically make it harmful. It simply changes it. For many people, those changes are irrelevant. For others, they are meaningful signals.

By understanding how reheating alters lectin activity, people gain another layer of control over their health. They can choose when leftovers make sense and when fresh preparation is worth the effort. They can batch cook strategically instead of assuming all leftovers are equal. Most importantly, they can stop blaming themselves for symptoms that have a biochemical explanation.

Food is not static. It is alive with chemistry long after it leaves the stove. Learning to work with that reality, rather than against it, is one of the most powerful steps anyone can take toward long-term digestive stability.