Fermentation is one of the oldest food preservation methods known to humanity, yet it continues to surprise modern researchers with how profoundly it reshapes the chemistry of what we eat. When it comes to high lectin foods, fermentation does something especially interesting. It transforms ingredients that may trouble sensitive individuals into gentler, more digestible versions of themselves. This transformation takes place quietly and invisibly, but inside every jar or crock, vast microscopic communities are breaking down lectins, altering nutrients, and reassembling the food in ways that nature never could achieve on its own.

Understanding how fermentation changes high lectin foods requires stepping inside that microbial world. It is a realm that operates through slow, patient work, powered by bacteria, yeasts, and molds that modify proteins, carbohydrates, and fibers. These small changes accumulate and eventually create something new. Fermented foods often taste better, digest more easily, and bring nutritional advantages that their raw forms do not offer. For anyone exploring a low lectin lifestyle, fermentation can become an important tool rather than an intimidating culinary experiment.

The Biology Behind Lectins and Why Fermentation Matters

Lectins are proteins that bind to carbohydrates. They exist in plants as natural defense molecules. Beans, grains, nightshades, and many seeds rely on lectins to discourage pests and help regulate their growth environment. These proteins are not inherently harmful for everyone, yet they can be irritating to the gut lining in a portion of the population. Their ability to attach to cell surfaces sometimes contributes to digestive discomfort or inflammation, especially when consumed in large quantities or in their raw or undercooked state.

This is where fermentation becomes relevant. Fermentation introduces controlled microbial activity that can modify protein structures through enzymatic action. Many of the bacteria involved in fermentation produce proteolytic enzymes, which break proteins into smaller fragments. Because lectins are proteins, they are subject to this transformation. In certain ingredients, particularly legumes and grains, fermentation has been shown to reduce lectin activity significantly by altering the proteins responsible for binding to carbohydrate structures.

Even though fermentation is not a blanket solution for every lectin-containing food, it plays a meaningful role in reducing some of the compounds that trigger digestive reactions. At the same time, fermentation does not merely remove things. It adds new layers of complexity to flavor, texture, and nutritional value.

How Microbes Transform High Lectin Foods at the Molecular Level

When food begins to ferment, microbes start to consume sugars and create acids, gases, and enzymes. These byproducts change the environment within the food. The pH drops, the structure of proteins loosens, and the overall biochemical composition shifts. For high lectin foods, this shifting environment can dramatically change how those lectins behave.

Microbial enzymes often cleave lectin proteins into smaller pieces. Once fragmented, lectins lose much of their ability to attach to intestinal receptors. This is one of the reasons why traditional cultures have fermented high lectin foods like soybeans for centuries. Soybeans contain complex lectins and other antinutrients, yet through long fermentation processes like those used in tempeh, miso, and natto, many of these compounds become less active.

Another benefit of fermentation is the growth of beneficial lactic acid bacteria. These microbes help further degrade lectins by lowering the pH. Many lectins are sensitive to acidic conditions and become inactive in more acidic environments. The extended exposure to low pH during fermentation helps neutralize lectins while simultaneously creating conditions that support digestion.

The process may look simple on the surface, but underneath, an entire chemical conversation unfolds. Microbes reshape the food according to their metabolic needs, and humans benefit from the results.

The Breakdown of Antinutrients Beyond Lectins

Lectins often share space with other antinutrients like phytates, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors. These compounds can interfere with nutrient absorption or irritate the digestive tract but respond well to fermentation.

For example, phytates bind minerals such as zinc and iron, making them harder for the body to absorb. Fermentation activates phytase enzymes that reduce phytate levels. This mineral releasing effect improves the nutritional quality of fermented foods compared to their unfermented versions. In legumes, this process is especially important because many of the nutrients become more available only after fermentation.

Trypsin inhibitors, another common antinutrient found in beans, block digestive enzymes that help break down proteins. Fermentation can significantly reduce these inhibitors, allowing the digestive system to function more smoothly. While fermentation is not the only method that breaks these compounds down, it often works in tandem with cooking or soaking to create a cumulative effect.

Because many consumers focus on lectins alone, the broader benefits of fermentation are sometimes overlooked. The reduction in multiple antinutrients makes fermented high lectin foods more nutrient dense overall, not just easier to digest.

Flavor and Texture Shifts as Indicators of Chemical Change

While the nutritional shifts inside fermented foods are fascinating on a biochemical level, the sensory transformation is what most people notice first. A fermented bean paste carries a deeper, more concentrated flavor than its raw counterpart. A fermented cassava dish takes on a softer texture. Fermented vegetables develop pleasant sourness and complexity.

These sensory changes are outward signs of interior transformations. When proteins break down, they form amino acids and peptides that contribute savory qualities. When carbohydrates ferment, lactic acid creates tang. When structural components soften due to microbial action, textures become more tender.

For high lectin foods in particular, texture change is often a sign that fermentation has loosened resistant structures. The same plant defenses that make certain foods difficult to digest also make them physically tough. Fermentation acts like a slow dismantling process that softens the scaffolding while adjusting the nutritional profile.

This is one reason traditional cuisines often pair fermentation with cooking. Fermentation unlocks the potential of the ingredient, and cooking then finishes the process by destroying any remaining lectin structures that survived microbial activity.

How Fermentation Supports Gut Health and Microbial Balance

In addition to modifying lectins directly, fermented foods introduce probiotics and metabolic byproducts that support digestive well-being. Many high lectin foods become not only safer but actively beneficial to the gut after fermentation.

Lactic acid bacteria present in fermented foods help colonize the digestive tract with microorganisms that can improve microbial diversity. A more balanced microbiome may help regulate inflammation and support digestion. At the same time, the acids produced during fermentation create a favorable environment for good bacteria while discouraging harmful species.

Short chain fatty acids, such as butyrate and acetate, often increase due to fermentation. These compounds support the gut barrier and help regulate immune signaling. Even if the fermented food no longer contains live probiotics after cooking, the fermentation metabolites remain in the dish and contribute to its health benefits.

The cumulative effect is that fermentation reshapes not just the food but also the experience of digesting it.

Traditional Foods That Demonstrate the Power of Fermentation

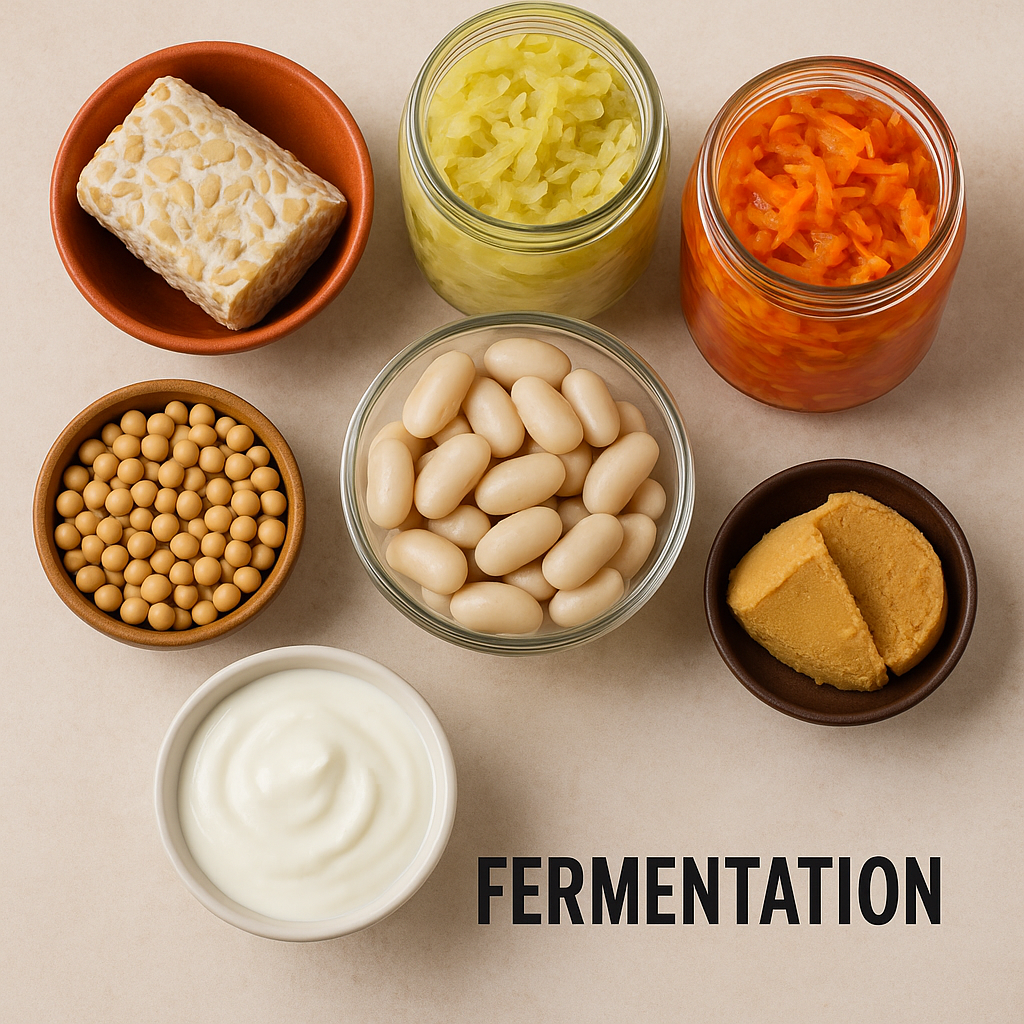

Human culinary history offers countless examples of fermentation taming or transforming ingredients that contain lectins. Soybeans are perhaps the most famous, but not the only example.

Tempeh relies on mold-based fermentation that knits soybeans together, breaks down lectins, and improves digestibility. Miso and natto involve bacteria and yeasts that reshape soybean proteins over an extended period. Each of these foods not only reduces lectin activity but also generates intense flavors and enhanced nutrition.

Other cultures have used fermentation to process cassava, which contains compounds that require careful preparation. Fermentation helps convert harmful precursors into safe forms, which is why cassava-based dishes vary so much from region to region depending on how long they ferment.

Even in grain-based foods like sourdough bread, fermentation softens proteins, breaks down gluten structures, and reduces antinutrients that interfere with digestion. Although grains are not universally tolerated, long fermentation often improves their nutrient profile when compared to quick-rise bread.

These examples show that fermentation is not a fringe technique. It is a foundational method that shapes food cultures worldwide, often solving nutritional challenges long before modern science could explain why it worked.

Modern Applications for a Low Lectin Lifestyle

For someone following a low lectin lifestyle, fermentation becomes a powerful ally. It allows individuals to enjoy modified versions of foods they might otherwise avoid, while also gaining the benefits of probiotic and prebiotic compounds.

Making fermented foods at home does not need to be complicated. Fermented vegetables, yogurt alternatives, and even simple bean ferments can be created with minimal tools. The key is paying attention to time, temperature, and salt concentration, since these control the microbial environment. For foods that contain significant lectins, combining fermentation with additional preparation steps such as soaking or pressure cooking provides the most reliable reduction.

Fermentation also introduces variety into a low lectin diet. Diversity in flavor, texture, and microbial exposure helps make the lifestyle sustainable in the long term. Since many gut issues respond not only to avoiding irritants but also to supporting beneficial bacteria, fermentation fits naturally into a balanced approach.

The Future of Research on Fermentation and Lectins

Although the traditional knowledge surrounding fermentation is vast, scientific research is still uncovering new details about how microbes dismantle antinutrients. Advanced tools now allow researchers to track changes at the molecular level and to identify specific compounds that decrease during fermentation.

As interest in gut health grows, scientists are beginning to explore how fermentation alters compounds beyond lectins and how those changes influence the microbiome. There is also new interest in designing targeted fermentation techniques that maximize lectin reduction for particular ingredients.

The more we learn, the clearer it becomes that fermentation is not just a culinary process. It is a biological partnership between humans and microorganisms. Understanding that partnership may offer new ways to improve food safety, nutrient absorption, and digestive comfort for individuals sensitive to lectins.

Conclusion

Fermentation is one of the most effective ways nature provides to reshape the nutritional profile of high lectin foods. Through slow microbial action, lectins lose their strength, antinutrients break down, nutrients become more accessible, and flavors deepen. Foods that once felt heavy or difficult become softer, more digestible, and sometimes even therapeutic for gut health.

Whether practiced in ancient kitchens or modern households, fermentation offers a safe and time-tested method to transform challenging ingredients into nourishing choices. For anyone navigating a low lectin lifestyle, it stands as a powerful tool that blends science, tradition, and sensory pleasure into a single transformative process.