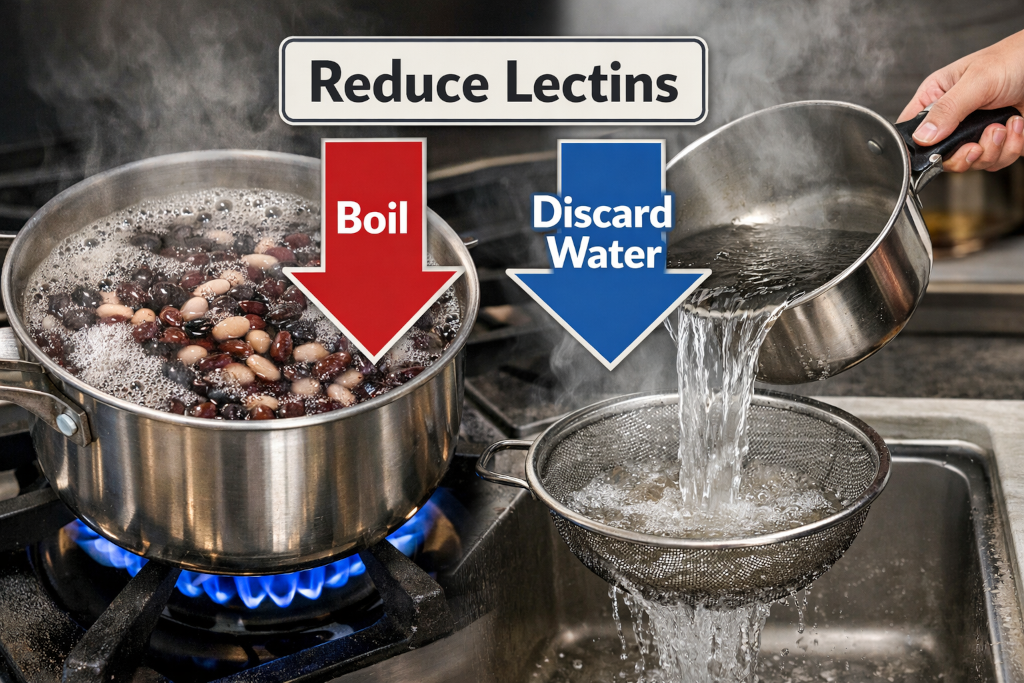

One of the simplest instructions you will see repeated in traditional cooking, ancestral food preparation, and modern low-lectin guidance is this: boil the food and discard the water. It sounds almost too basic to matter. In a world of complex nutrition debates, enzyme supplements, and lab-driven food trends, pouring water down the drain can feel insignificant.

Yet this practice survives across cultures for a reason. It is not culinary superstition, nor is it a modern health fad. Boiling and discarding water works because it takes advantage of very real physical and chemical properties of food compounds, especially lectins and related anti-nutrients that respond predictably to heat and water.

Understanding why this works helps explain why certain foods are better tolerated when prepared this way, why slow cookers and pressure cookers are often recommended, and why simply “eating clean” is not always enough for people struggling with digestive or inflammatory symptoms.

This is not about demonizing foods. It is about understanding how preparation changes what those foods do once they enter your body.

Why Plants Defend Themselves in the First Place

Lectins are not toxins in the dramatic sense. They are carbohydrate-binding proteins that plants produce as part of their defense system. Plants cannot run from predators, so they rely on chemical deterrents to discourage being eaten or to limit digestion in insects, animals, and microbes.

In seeds, grains, legumes, and some vegetables, lectins help protect the next generation of the plant. From the plant’s perspective, they are doing their job well.

From a human perspective, problems arise because lectins can bind to the cells lining the digestive tract. In susceptible individuals, this binding may interfere with nutrient absorption, irritate the gut lining, or interact with immune signaling. The result can be bloating, joint discomfort, fatigue, skin reactions, or brain fog. These symptoms are real, even if they vary widely from person to person.

The key point is this: lectins are structurally sensitive to heat and water. They are not immutable. Their activity can be reduced, altered, or neutralized through proper preparation.

Heat Changes Protein Shape

Lectins are proteins, and proteins are not rigid objects. Their biological activity depends on their three-dimensional structure. When that structure changes, their ability to bind to carbohydrates and to human tissue changes as well.

Heat disrupts the weak bonds that hold proteins in their active shape. This process is called denaturation. It does not destroy the protein entirely, but it can render it biologically inactive.

Dry heat alone can denature some lectins, but moist heat is far more effective. Water transfers heat more evenly and penetrates food more thoroughly, especially in dense foods like beans and grains. That is why boiling, pressure cooking, and long simmering outperform baking or light sautéing when it comes to lectin reduction.

Why Water Matters Just as Much as Heat

Heat weakens lectins, but water gives them somewhere to go.

Many lectins and related compounds are water-soluble. When food is soaked or boiled, these compounds can leach out into the surrounding liquid. This is especially true during prolonged cooking, when cell walls break down and internal components are released.

If that liquid is consumed, the compounds are still present, just redistributed. If the liquid is discarded, the total lectin load of the meal is reduced.

This is the core logic behind boiling and discarding water. You are not just altering the food internally; you are physically removing a portion of the compounds that cause problems for sensitive people.

Traditional Cooking Already Knew This

Long before anyone understood proteins or carbohydrate binding, traditional cuisines developed methods that worked.

Beans were soaked overnight and boiled in fresh water. Bitter vegetables were parboiled. Starchy roots were leached in water before cooking. Broths were often made from low-lectin components rather than from the soaking liquid of legumes.

These practices emerged through observation. People noticed which foods caused discomfort and which preparations reduced it. Over generations, techniques that worked survived.

Modern food systems disrupted this knowledge by prioritizing speed and convenience. Canned beans, quick-cook grains, and microwave meals removed preparation steps that once served a biological purpose.

Boiling and discarding water is not a new rule. It is a return to an older understanding.

Soaking vs Boiling: Different Roles, Same Goal

Soaking and boiling are often discussed together, but they do slightly different things.

Soaking initiates hydration and begins the leaching process. Water-soluble lectins and enzyme inhibitors diffuse into the soak water over time. This reduces the burden before heat is even applied.

Boiling completes the job by denaturing remaining lectins through sustained heat while continuing to draw them into the cooking liquid.

Using both steps together is far more effective than either alone. Soaking without boiling leaves active lectins behind. Boiling without discarding water neutralizes some activity but keeps soluble compounds in the meal.

The combination matters.

Why Pressure Cooking Works So Well

Pressure cooking deserves special mention because it consistently shows superior results in lectin reduction.

Under pressure, water boils at a higher temperature. This allows food to reach temperatures that are not possible with standard boiling, without drying out. Lectins that resist lower temperatures are more likely to be denatured under these conditions.

This is why pressure-cooked beans are often better tolerated than slow-cooked or baked versions, even when all other variables are the same.

The mechanism is not mysterious. It is physics applied to food.

Vegetables Are Not Exempt

Lectins are often discussed in the context of legumes, but many vegetables contain them as well. Especially true when eaten raw or lightly cooked.

Boiling vegetables and discarding the water can reduce lectins, oxalates, and other irritants simultaneously. This is particularly relevant for people who react to foods that are otherwise considered “healthy.”

For some individuals, raw salads are harder to tolerate than cooked vegetables. This is not a failure of willpower or gut health. It is a mismatch between preparation and physiology.

Cooking changes the biological conversation between food and body.

What Happens When the Water Is Kept

It is important to understand that not all cooking liquids are harmful. Bone broths, meat stocks, and vegetable broths made from low-lectin ingredients can be nourishing.

The issue arises when the liquid contains compounds you are actively trying to reduce.

If beans are boiled and the water is used as soup base, the lectins did not disappear. They migrated. The same applies to slow cooker recipes where legumes simmer for hours in the same liquid that is ultimately consumed.

For people without sensitivity, this may not matter. For those managing lectin-related symptoms, it often does.

Modern Research Supports the Old Methods

Laboratory studies consistently show that moist heat reduces lectin activity. The degree of reduction depends on temperature, time, and whether the cooking medium allows compounds to diffuse away from the food.

No single preparation method eliminates all lectins, and not all lectins behave the same way. But the trend is clear: boiling and discarding water significantly lowers exposure.

This aligns with clinical observations where people report improved tolerance when foods are prepared traditionally rather than quickly or minimally.

Science is not discovering something new here. It is explaining something old.

Why This Matters Beyond Digestion

Lectins do not only affect the gut. Because the digestive tract is closely tied to immune signaling, metabolic regulation, and even neurological communication, irritation at the gut level can echo throughout the body.

Reducing lectin load can indirectly support better sleep, more stable energy, and fewer inflammatory flare-ups for some individuals. This does not mean lectins are the root cause of all symptoms, but they can be a contributing factor in an already stressed system.

Preparation becomes a lever that is small, mechanical, and repeatable, as well as changes how food interacts with the body.

The Bigger Picture of Food Preparation

Boiling and discarding water is not a cure, and it is not required for every food or every person. It is one tool in a broader framework that includes ingredient selection, cooking methods, lifestyle factors, and individual tolerance.

What makes it powerful is its simplicity. It does not require supplements, testing, or expensive products. It relies on physics, chemistry, and time.

For people exploring a low-lectin approach, understanding this process transforms it from a rule into a reasoned choice.

A Practical Takeaway

If you remove one idea from this discussion, let it be this: food is not static. Its biological effects are shaped long before it reaches your plate.

Boiling and discarding water works because it respects how proteins behave, how compounds dissolve, and how the body responds to what it absorbs. It is not about fear. It is about alignment between preparation and physiology.

Once you understand that, the practice stops feeling restrictive and starts feeling intentional.

And in nutrition, intention often matters more than perfection.