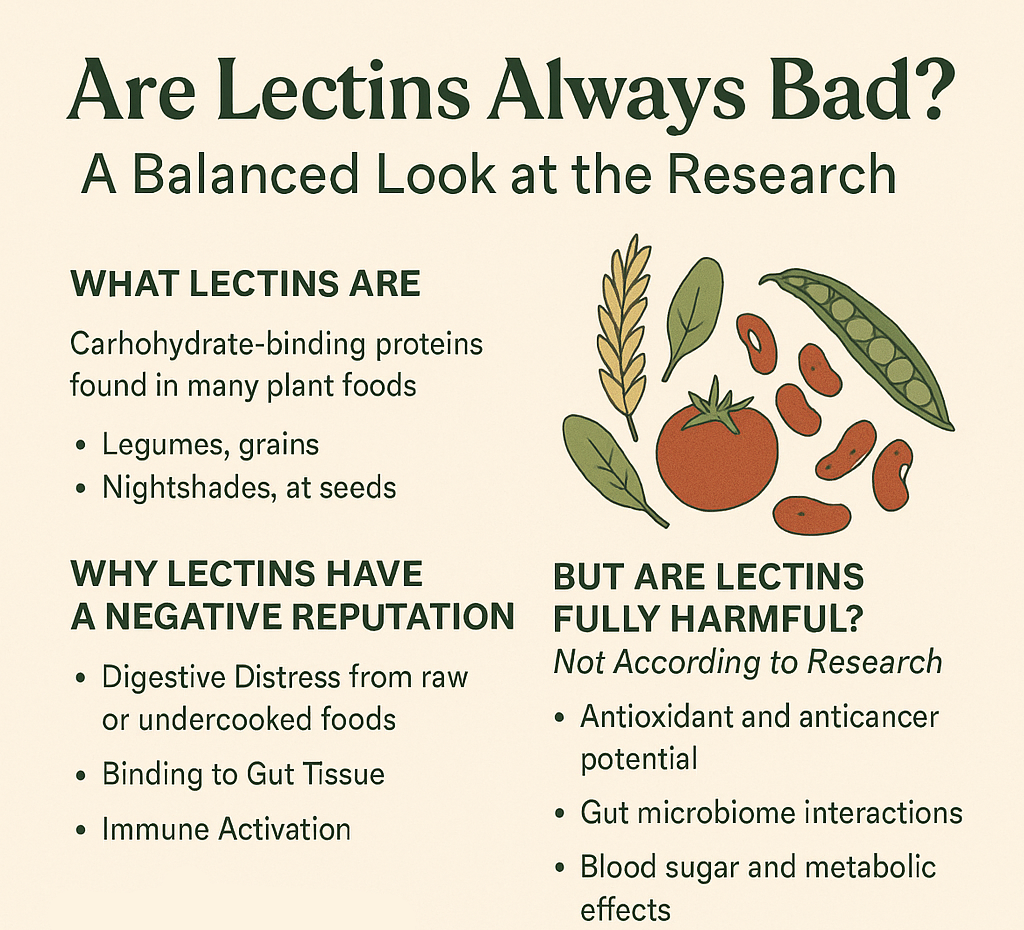

Lectins have become something of a dietary villain in recent years. They’re blamed for digestive discomfort, inflammation, autoimmune flares, and weight issues. Yet lectins are found in hundreds of whole foods eaten around the world every day, many of which are considered nutrient-dense and beneficial. How do we reconcile these two realities? Are lectins universally harmful, or do they affect different people in different ways? And what does the science actually say?

The answer, as usual in nutrition, is far more nuanced than a simple “good” or “bad.” Lectins are a naturally occurring family of proteins, and their impact on the body depends heavily on the type of lectin, the food it comes from, and how that food is prepared. While some lectins can irritate the gut and trigger immune responses, many others are harmless and some even have promising therapeutic effects in early studies.

This balanced overview explores what lectins are, how the body interacts with them, what the latest research suggests, and why a low-lectin lifestyle can be helpful for some people without condemning all lectin-containing foods across the board.

What Lectins Actually Are

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins found in plants, animals, fungi, and even bacteria. In plants, they serve several purposes:

- Defense: discouraging insects and predators

- Seed survival: helping seeds remain intact through digestion

- Signaling: guiding plant cell interactions

Legumes, grains, nightshades, and many seeds contain naturally higher levels of lectins. Some of the most commonly discussed dietary lectins include:

- Phytohemagglutinin (red kidney beans)

- Wheat germ agglutinin (wheat)

- Solanaceous lectins (tomatoes, peppers, potatoes)

- Peanut agglutinin (peanuts)

The key is that lectins behave differently depending on structure and concentration. Not all lectins have the same biological effects, which is why broad generalizations often miss the mark.

Why Lectins Have a Negative Reputation

1. Digestive Distress From Raw or Undercooked Foods

Certain lectins are known to irritate the digestive tract when consumed in high amounts or in improperly cooked foods. Undercooked kidney beans are a well-known example. Ingesting them can lead to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea because the lectin phytohemagglutinin can disrupt the lining of the gut.

But cooking makes all the difference. Proper boiling or pressure cooking destroys up to 99% of the active lectins, making foods like beans and lentils safe and nutritious.

2. Binding to Gut Tissue

Some lectins can bind to the intestinal wall, interfering with nutrient absorption or irritating the gut barrier. Individuals with leaky gut, IBS, Crohn’s, or other inflammatory gut conditions may be especially sensitive, which is one of the key motivations behind adopting a low-lectin diet.

3. Immune Activation

Because lectins interact with glycoproteins on cell surfaces, they can stimulate immune activity. For most people this isn’t a problem, but sensitive individuals may experience:

- Joint pain

- Bloating

- Fatigue

- Skin issues

- Exacerbated autoimmune symptoms

This does not mean lectins universally trigger autoimmune disease but people with existing issues sometimes see improvement when reducing high-lectin foods.

But Are Lectins Fully Harmful? Not According to Research

When studied in controlled environments, certain lectins appear to have potential health benefits, depending on dosage and form.

1. Antioxidant and Anticancer Potential

Some lectins can help the body recognize and eliminate abnormal cells. Laboratory studies (not yet large human trials) have found:

- Certain mushroom and legume lectins show anti-tumor activity

- Some lectins may stimulate the immune system to target cancer cells

- Plant lectins may regulate cell growth pathways

This doesn’t mean lectins cure cancer but it highlights their complexity and biological diversity.

2. Gut Microbiome Interactions

Not all lectins harm the gut. Some fermentable plant lectins may:

- Feed beneficial gut bacteria

- Support short-chain fatty acid production

- Improve microbial diversity

This may help explain why populations consuming lectin-rich foods (beans, whole grains, vegetables) often have better metabolic health and longevity when their diets also include proper cooking methods and balanced variety.

3. Blood Sugar and Metabolic Effects

Lectins that survive digestion partially may slow carbohydrate absorption, potentially stabilizing blood sugar. This is sometimes framed as a negative, but it can also be protective in certain metabolic contexts.

4. Role in Immune System Development

Small exposures to plant lectins early in life may help “train” the immune system. This is similar to how low-level exposure to environmental microbes supports immune resilience.

Why Some People React and Others Don’t

The research makes one theme clear: individual variability matters.

Factors influencing lectin sensitivity include:

1. Gut Barrier Integrity

A healthy, intact intestinal lining prevents most lectins from entering the bloodstream. If you have:

- Increased intestinal permeability

- History of gut infections

- High stress

- Chronic NSAID use

- Autoimmune conditions

…you may react more strongly to lectins than someone with a robust gut barrier.

2. Microbiome Composition

A diverse microbiome may break down lectins more efficiently.

3. Genetic Factors

Variations in immune system signaling or glycoprotein structure may alter how a person responds.

4. Food Preparation Habits

Traditional methods such as:

- Pressure cooking beans

- Peeling and deseeding nightshades

- Fermenting grains or vegetables

- Soaking or sprouting seeds

…dramatically reduce lectin content.

People who grow up with these preparation techniques often tolerate high-lectin foods much better.

How Lectins Are Reduced Through Cooking and Processing

One of the most important points in the entire lectin discussion is this: cooking changes everything.

- Pressure Cooking – Destroys the majority of lectins in beans, lentils, potatoes, and tomato sauces.

- Boiling – Neutralizes harmful lectins in kidney beans and most legumes when cooked thoroughly.

- Fermentation – Breaks down lectins in grains and vegetables while increasing probiotic content.

- Soaking and Sprouting – Reduces lectins by activating enzymes within the plant.

- Peeling and Deseeding – Nightshades store most lectins in the skin and seeds; removing them dramatically lowers lectin load.

These are the techniques emphasized in low-lectin cooking because they support easier digestion, especially for people with gut issues.

Modern Diet vs. Traditional Diet

One reason lectins have become a modern health concern is that traditional food preparation methods are no longer common in industrialized food culture.

Our ancestors:

- soaked beans overnight

- fermented grains

- pressure cooked or slow simmered dishes

- milled or peeled grains and seeds

Modern diets often rely on:

- ultraprocessed foods

- undercooked convenience meals

- raw grains or legumes in trendy health foods (e.g., raw sprouted wheat crackers, raw peanut flours)

This mismatch between ancient lectin-containing foods and modern preparation shortcuts may explain why lectin sensitivity seems to be increasing.

The Argument For Lectin Reduction

A low-lectin lifestyle isn’t about demonizing foods. It’s about identifying which foods or preparation methods support digestion, reduce inflammation, and enhance energy for people who are sensitive.

Common reported benefits include:

- Less bloating

- Reduced joint pain

- Improved mental clarity

- Fewer autoimmune flares

- Better overall digestion

These improvements make logical sense when you consider the effects lectins can have on the gut lining and immune system in susceptible individuals.

The Argument Against Demonizing All Lectins

On the other hand, eliminating every lectin-containing food would remove many nutritious staples:

- Beans and lentils

- Tomatoes

- Potatoes

- Peppers

- Whole grains

- Certain nuts and seeds

Many cultures with exceptional longevity, such as Blue Zones, eat high-lectin foods regularly but in traditionally prepared forms.

This suggests that lectins are not the sole villain; rather, issues arise when:

- the gut is already inflamed

- lectin-heavy foods are eaten raw or improperly prepared

- there is a genetic predisposition

- a person’s microbiome is compromised

Balance and personalization matter.

A Balanced Framework: When Lectins May Be Problematic

A lectin-conscious lifestyle may be especially beneficial if you have:

- autoimmune disease

- digestive disorders

- chronic inflammation

- food sensitivities

- unexplained fatigue

- joint or muscle pain

- symptoms that worsen after eating beans, grains, or nightshades

In these cases, reducing lectins is a diagnostic tool as much as a lifestyle.

A Balanced Framework: When Lectins Are Less Likely to Be an Issue

You may tolerate lectins well if you:

- have no digestive complaints

- have a diverse microbiome

- eat traditionally prepared whole foods

- do not experience autoimmune symptoms

- have strong metabolic health

For these individuals, high-lectin foods can remain part of a nutritious diet.

The Middle Path: The Low-Lectin Approach as a Targeted Strategy, Not a Universal Rule

The goal is not to eliminate lectins forever. It’s to reduce inflammatory load and improve gut health, then reintroduce foods carefully to identify what your body can tolerate.

This personalized approach recognizes that:

- Beans may be fine for some people after pressure cooking

- Tomatoes may only be problematic when skins and seeds are intact

- Peanuts may cause inflammation in some, but not all, individuals

- Wheat lectins may cause reactions unrelated to gluten

Rather than treating lectins like an all-or-nothing issue, a phased method allows you to build a diet that supports your body without unnecessary restriction.

What the Emerging Research Suggests

Science is still evolving, but current evidence supports these conclusions:

- Lectins are biologically active, not inherently harmful. They have diverse effects; some negative, some neutral, some beneficial.

- Food preparation determines lectin levels dramatically. Traditional methods neutralize most harmful lectins.

- The gut barrier is the gatekeeper. Lectins only become problematic when they interact with vulnerable intestinal tissue.

- Individual variability is significant. Two people can eat the same tomato sauce and have completely different responses.

- More long-term human studies are needed. Animal studies and cell studies show mechanisms, not real-world dietary outcomes.

So… Are Lectins Always Bad? No. And that’s exactly the point. Lectins are not universally harmful, but they are not universally harmless either. They exist in a gray zone where biology, genetics, gut health, and cooking methods interact to determine their impact.

For some people, reducing lectins, especially the most active ones, can be life-changing. For others, lectin-rich foods remain a healthy part of a varied diet. The goal is informed choice, not restriction for restriction’s sake. A low-lectin lifestyle simply gives you the tools to remove the foods that inflame your system while keeping those that nourish you.

Final Thoughts

Lectins are a reminder of how complex nutrition truly is. Instead of categorizing foods as “good” or “bad,” a better question is:

How does this food interact with my body?

Your gut, your microbiome, your immune system, and your health history make this a deeply personal equation. A balanced look at lectins shows that they can be problematic for some, neutral for many, and potentially beneficial in certain contexts, especially when prepared correctly.

The key is understanding your own tolerance, making intentional choices, and using a low-lectin approach as a tool to promote long-term digestive and metabolic health.