Digestion is often imagined as a powerful, unforgiving process. Food enters the mouth as something recognizable and exits the stomach and intestines as broken-down nutrients, reduced to amino acids, fatty acids, and simple sugars. This mental picture suggests that nothing complicated survives the journey intact. Yet some compounds do. Among them are lectins, plant proteins that have drawn growing attention for their ability to resist digestion and interact with the body in ways that go far beyond basic nutrition.

Lectins are not accidental contaminants in food. They are purposeful molecules produced by plants as part of their defense system. Over millions of years, plants evolved chemical strategies to discourage animals, insects, and microbes from eating them. Lectins serve this role by binding to carbohydrates on the surfaces of cells. This binding ability is what makes them biologically active, and it is also what allows many lectins to persist through digestion largely intact.

Understanding how lectins survive digestion requires stepping back from the idea that digestion is a universal eraser. The digestive system is powerful, but it is also selective. It evolved to process foods humans have historically eaten in certain forms and quantities. Lectins challenge this system precisely because they were never meant to nourish the organism consuming them.

The Structural Advantage of Lectins

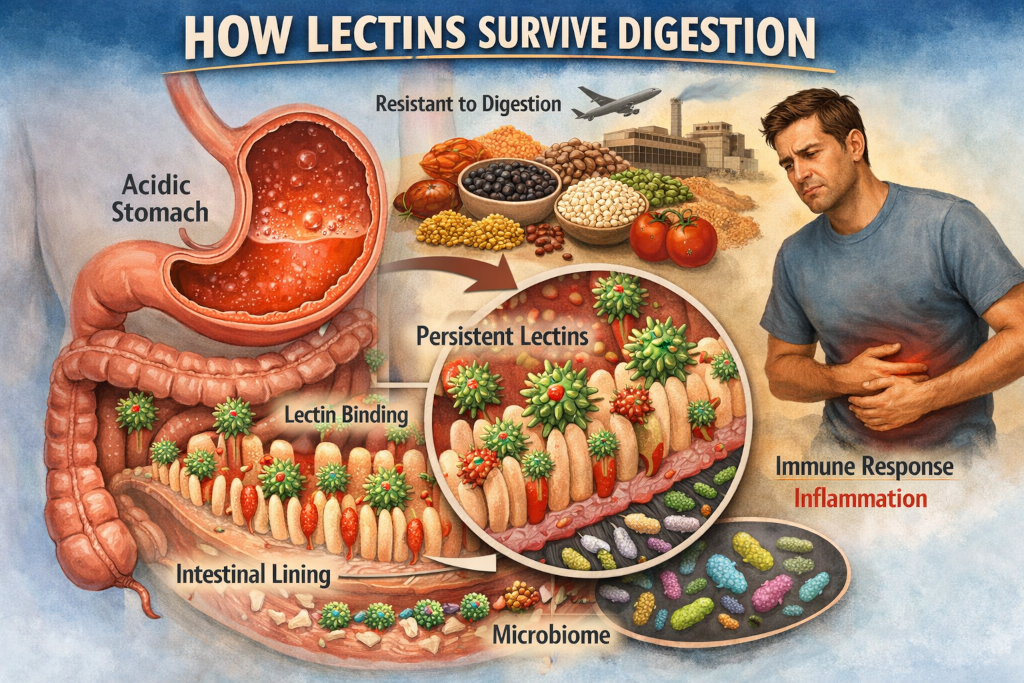

Proteins are typically vulnerable to digestion. Enzymes like pepsin in the stomach and proteases in the small intestine are designed to break proteins into smaller fragments. Lectins, however, often possess tightly folded structures stabilized by multiple disulfide bonds. These chemical bonds act like internal braces, making the protein more resistant to heat, acid, and enzymatic attack.

This structural stability means that while some lectins are partially broken down during digestion, others remain functionally intact. Even fragments of lectins can retain their carbohydrate-binding ability, which is the key feature that allows them to interact with intestinal cells.

Not all lectins behave the same way. Some are easily deactivated by cooking, soaking, or fermentation. Others are far more resilient. This variability explains why lectins cannot be treated as a single nutritional category. Their survival depends on their source, structure, and how the food is prepared.

The Journey Through the Stomach

The stomach is acidic by design. Its low pH denatures many proteins, unfolding them so enzymes can access their internal bonds. Lectins, however, are often acid-resistant. Their folded shapes are less likely to unravel in harsh conditions, allowing them to pass through the stomach with their functional domains intact.

This does not mean lectins are completely untouched. Some damage occurs. But survival does not require perfection. A lectin that emerges partially intact can still bind to carbohydrates in the intestine and exert biological effects.

This challenges a common assumption: that digestion neutralizes all potential food-related threats. In reality, digestion evolved to extract energy and nutrients, not to deactivate every defensive compound plants produce.

Interaction With the Intestinal Lining

Once lectins reach the small intestine, their real influence begins. The intestinal lining is covered in carbohydrate-rich structures known as glycoproteins. These carbohydrates play roles in cell signaling, immune communication, and nutrient absorption. Lectins are drawn to these structures like magnets.

By binding to the intestinal lining, lectins can resist being flushed away with digested food. Instead, they may adhere temporarily to the gut wall. This binding can interfere with normal cellular processes, including nutrient absorption and barrier function.

In some individuals, lectin binding may increase intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut.” This is not a guaranteed outcome, nor does it occur equally in everyone. Genetics, gut health, microbiome composition, and dietary context all influence how the body responds.

What matters is that lectins do not need to be absorbed into the bloodstream to have an effect. Their interaction with the gut itself is enough to influence immune signaling and digestive comfort.

Why Cooking Helps but Does Not Always Solve the Problem

Traditional food preparation methods exist for a reason. Soaking, fermenting, pressure cooking, and sprouting were developed long before modern nutrition science. These techniques reduce lectin activity by altering protein structures, breaking down binding sites, or leaching lectins into cooking water.

Heat denatures many lectins, but not all heat is equal. Boiling may reduce lectin content significantly in some foods, while dry heat may be less effective. Pressure cooking is particularly powerful because it combines high heat with moisture, disrupting even stubborn protein structures.

Still, cooking does not create uniform results. Some lectins survive standard cooking methods, especially when foods are undercooked or processed in ways that preserve protein integrity. Modern food systems sometimes prioritize texture, shelf stability, and speed over traditional preparation, unintentionally preserving lectin activity.

This helps explain why two people can eat the same food prepared in different ways and experience vastly different outcomes.

The Role of the Microbiome

The gut microbiome adds another layer to the story. Certain bacteria can degrade lectins or reduce their binding potential. Others may be negatively affected by lectins, leading to shifts in microbial balance.

A healthy, diverse microbiome may buffer some of the effects of lectins by breaking them down more efficiently or limiting their interaction with the gut lining. Conversely, a disrupted microbiome may amplify lectin sensitivity.

This relationship helps explain why lectin tolerance can change over time. Illness, antibiotics, stress, sleep deprivation, and dietary changes all affect microbial composition. As the microbiome shifts, so does the body’s ability to handle lectins.

Lectin survival, therefore, is not just about the protein itself. It is about the ecosystem it enters.

Absorption and Systemic Effects

While most lectins exert their effects locally in the gut, some can cross the intestinal barrier in small amounts. This is more likely when the barrier is already compromised. Once in circulation, lectins may interact with immune cells or tissues that display compatible carbohydrate structures.

This does not mean lectins automatically cause disease. It means they have the potential to participate in immune signaling under certain conditions. For individuals with autoimmune tendencies or chronic inflammation, this interaction may be more noticeable.

The body recognizes lectins as foreign. Repeated exposure can provoke immune responses in susceptible individuals, particularly when lectin intake is high and preparation methods are inadequate.

Why Humans Notice Lectins Now More Than Before

Lectins are not new. What is new is the scale and form in which people consume them. Modern diets rely heavily on grains, legumes, and processed plant-based foods. Many of these foods are consumed daily, sometimes multiple times per day, and often in forms that minimize traditional preparation steps.

Food distribution systems prioritize convenience and shelf life. This means shorter soaking times, quicker cooking, and fewer fermentation processes. The result is a higher likelihood that active lectins reach the digestive tract.

At the same time, modern life introduces factors that compromise gut resilience. Chronic stress, poor sleep, environmental toxins, and ultra-processed foods all strain the digestive system. In this context, lectins are more likely to survive digestion and interact with the body in noticeable ways.

This does not imply that all plant foods are harmful or that lectins should be feared. It suggests that context matters. How food is grown, processed, prepared, and consumed shapes how the body responds.

Individual Sensitivity and the Illusion of Universality

One of the most confusing aspects of lectins is inconsistency. Some people eat high-lectin foods with no obvious issues. Others experience bloating, joint discomfort, skin reactions, or fatigue.

This variability does not invalidate lectin research. It reflects biological diversity. Digestive enzyme levels, gut integrity, immune sensitivity, and microbiome composition differ widely among individuals.

Lectins survive digestion because they are designed to. Whether that survival becomes a problem depends on the internal environment they encounter.

Understanding this shifts the conversation away from rigid dietary rules and toward informed experimentation. Reducing lectin exposure through preparation methods or selective avoidance becomes a tool, not a doctrine.

Reframing Digestion as a Dialogue

Digestion is not a simple breakdown process. It is a dialogue between food and body, shaped by evolution, environment, and individual biology. Lectins survive digestion not because the system is broken, but because plants evolved effective defense strategies and humans changed how food is prepared and consumed.

Recognizing this allows for nuance. Lectins are neither imaginary villains nor harmless passengers. They are biologically active compounds that demand respect and understanding.

By learning how lectins survive digestion, people gain insight into why certain foods feel nourishing while others feel disruptive. This awareness empowers better choices, grounded not in fear, but in physiology.

In the end, the question is not whether lectins survive digestion. Many do. The more important question is whether the digestive system is prepared to handle them and what steps can be taken to restore that balance when it is not.