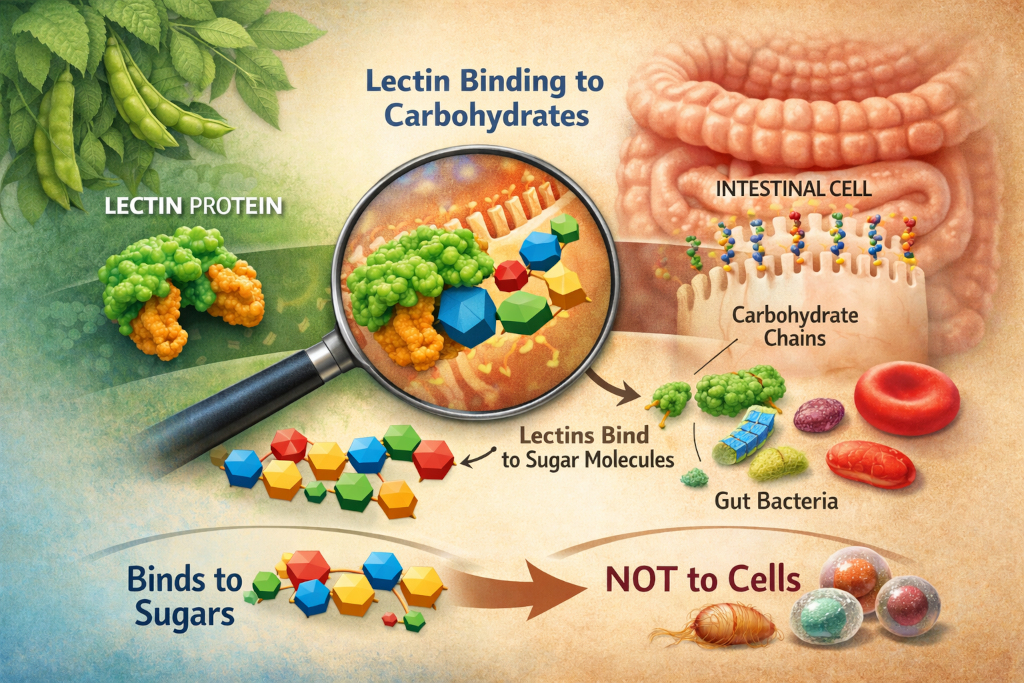

When people first encounter the topic of lectins, they are often told a simplified version of the story: lectins “stick to cells,” disrupt digestion, or irritate the gut lining. While that description is not entirely wrong, it misses the most important and fascinating detail. Lectins do not bind to cells themselves. They bind to carbohydrates, specific sugar structures that happen to be displayed on the surface of cells.

This distinction matters. Understanding why lectins bind to carbohydrates rather than directly to cells changes how we think about food, digestion, immune signaling, and even plant evolution. It also explains why lectins can affect different people in different ways, why cooking methods matter, and why some lectin interactions are far more complex than a simple “good” or “bad” label.

To understand lectins properly, we need to move away from the idea that they are blunt toxins or accidental dietary hazards. Lectins are highly selective molecules, shaped by millions of years of biological interaction. Their preference for carbohydrates is not incidental. It is the entire point.

Carbohydrates as Biological Information

In everyday nutrition discussions, carbohydrates are usually framed as fuel. Sugars and starches are something we burn for energy, something to limit or count, something that raises blood glucose. In biology, however, carbohydrates play a much deeper role.

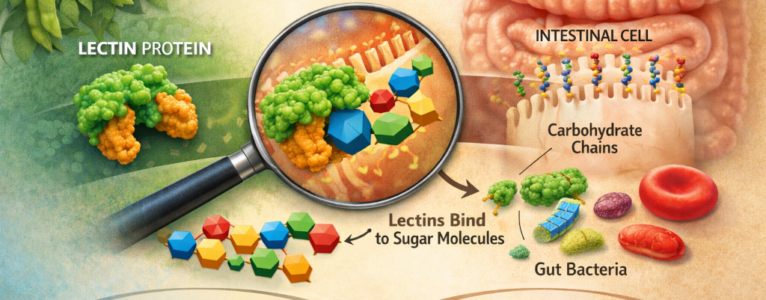

On the surface of nearly every cell in the human body and in plants, animals, bacteria, fungi, and viruses, there are complex carbohydrate chains attached to proteins and fats. These structures form what is known as the glycocalyx, a dense sugar coating that functions as a biological identification system. These carbohydrate patterns tell the immune system whether a cell is “self” or “foreign,” help cells communicate with one another, and influence how microbes interact with host tissues.

In other words, carbohydrates are not just food. They are signals. Lectins evolved to read those signals.

Why Plants Developed Carbohydrate-Binding Proteins

Plants are stationary organisms. They cannot run from predators, fight back physically, or change environments when conditions become hostile. Their survival depends on chemistry. Over evolutionary time, plants developed a sophisticated arsenal of defensive compounds, including bitter alkaloids, enzyme inhibitors, antimicrobial peptides, and lectins.

Lectins occupy a unique niche in this defense system. Instead of poisoning indiscriminately, lectins act more like molecular sensors. By binding to specific carbohydrate patterns, they can recognize insects, fungi, bacteria, and grazing animals at the molecular level.

This carbohydrate specificity allows lectins to interfere with biological processes that depend on sugar-mediated recognition. In insects, lectins may bind to carbohydrates in the gut lining, disrupting nutrient absorption or triggering immune stress. In microbes, lectins can interfere with cell wall integrity or adhesion. In mammals, lectins can survive digestion long enough, under certain conditions, to interact with carbohydrate structures along the intestinal surface. Plants did not evolve lectins with human digestion in mind. Humans simply inherited the consequences of consuming molecules designed for ecological defense.

Lectins Do Not Target Cells, They Target Patterns

One of the most persistent misunderstandings about lectins is the idea that they “attack” cells. In reality, lectins have no awareness of cells as entities. What they recognize are specific carbohydrate motifs. A lectin molecule has one or more carbohydrate-binding domains shaped to fit particular sugar arrangements, much like a lock fits a key. These sugar structures can appear on the surface of cells, within mucus layers, on bacterial membranes, or attached to dietary particles passing through the gut.

If the carbohydrate pattern matches the lectin’s binding preference, attachment occurs. If it does not, the lectin passes by without interaction.

This explains why lectins behave differently in different tissues, species, and individuals. It also explains why some lectins bind strongly to red blood cells (a property historically used in blood typing research), while others preferentially bind to intestinal epithelial sugars or microbial surfaces. The lectin is not “choosing” a cell. It is responding to a sugar code.

The Gut Lining as a Carbohydrate-Rich Interface

The human intestinal lining is one of the most carbohydrate-dense environments in the body. The surface of intestinal cells is coated in glycoproteins and mucins which are long, sugar-rich molecules that form a protective mucus layer. This layer serves as both a barrier and a communication interface between the body and the external world.

From the plant’s evolutionary perspective, this sugar-rich surface is an opportunity. When certain lectins reach the gut intact, they can bind to these carbohydrate structures. In some cases, this binding is transient and harmless. In other cases, particularly when the gut barrier is already compromised, lectin attachment may contribute to irritation, immune activation, or altered permeability.

Importantly, the lectin is not damaging tissue by force. Any disruption occurs as a downstream effect of carbohydrate binding that interferes with signaling pathways, nutrient transport, or immune recognition. This distinction matters because it shifts the focus from lectins as invaders to lectins as interactors. The outcome depends on context.

Why Cooking and Processing Change Lectin Behavior

Lectins are proteins, and like all proteins, their function depends on structure. Heat, pressure, acidity, and enzymatic activity can alter or destroy the precise shape required for carbohydrate binding. When lectins are denatured through cooking methods such as pressure cooking, long soaking, fermentation, or sprouting, their carbohydrate-binding domains may be partially or fully disrupted. Without that precise structural fit, lectins lose much of their biological activity.

This is why traditional food preparation methods evolved independently across cultures. Long before anyone understood molecular biology, humans learned through trial and error that certain foods were safer or more tolerable when prepared in specific ways. Those methods often targeted the structural integrity of lectins, even if the mechanism was unknown at the time. Understanding lectins as carbohydrate-binding proteins explains why preparation matters more than simple avoidance in many cases.

Individual Variation and Carbohydrate Expression

Not all people express the same carbohydrate patterns on their cells. Genetics, blood type, microbiome composition, age, health status, and environmental exposure all influence the glycosylation patterns, the sugar decorations, on cell surfaces.

This variability helps explain why lectins affect people differently. A lectin that binds strongly to one individual’s intestinal carbohydrates may have little affinity for another’s. Differences in gut mucus thickness, microbial competition, and immune signaling further modify outcomes.

This is one reason why lectin sensitivity cannot be reduced to a universal rulebook. The interaction is biochemical, not moral. It is shaped by both the lectin’s binding specificity and the host’s carbohydrate landscape. Understanding this helps move the conversation away from fear and toward informed experimentation.

Lectins, Microbes, and Competitive Binding

The gut microbiome adds another layer of complexity. Many gut bacteria also display carbohydrate structures on their surfaces and many produce their own lectins or lectin-like proteins. This creates a competitive environment where binding sites are constantly occupied, blocked, or modified.

In some cases, microbial carbohydrates may act as decoys, binding dietary lectins before they reach the intestinal lining. In other cases, lectins may preferentially bind microbial surfaces, altering microbial composition indirectly.

This dynamic interaction is an active area of research. What is becoming increasingly clear is that lectins do not operate in isolation. Their effects are mediated by the ecosystem they enter. Understanding lectin-carbohydrate binding helps explain why gut health, microbial diversity, and dietary context all influence lectin tolerance.

Moving Beyond the “Lectins Stick to Cells” Narrative

Saying that lectins “stick to cells” is like saying a key “sticks to doors.” It is technically true at a surface level, but it misses the mechanism entirely.

Lectins bind to carbohydrates because carbohydrates are the language of biological recognition. Cells, microbes, and tissues all display sugar patterns that convey identity, status, and function. Lectins evolved to read that language.

Once we understand this, the conversation around lectins becomes more nuanced and less reactionary. Lectins are not villains hiding in food. They are signaling molecules interacting with signaling systems. Whether those interactions are beneficial, neutral, or problematic depends on preparation, quantity, individual biology, and overall context.

Why This Perspective Matters for a Low-Lectin Lifestyle

A low-lectin approach is not about eliminating plants or fearing food. It is about understanding molecular interactions well enough to reduce unnecessary stress on the body while preserving nutritional diversity.

By recognizing that lectins bind to carbohydrates, not cells, we gain a framework for making practical decisions. We can focus on cooking methods that disrupt binding. We can pay attention to gut health and recovery. We can approach food reactions as data rather than diagnoses.

Most importantly, we can stop treating lectins as mysterious threats and start treating them as understandable biological tools, tools that make sense once we learn the language they speak. Lectins bind to carbohydrates because carbohydrates are where biology stores information. Once you see that, the entire lectin discussion shifts from fear to comprehension.

And comprehension is where real dietary empowerment begins.