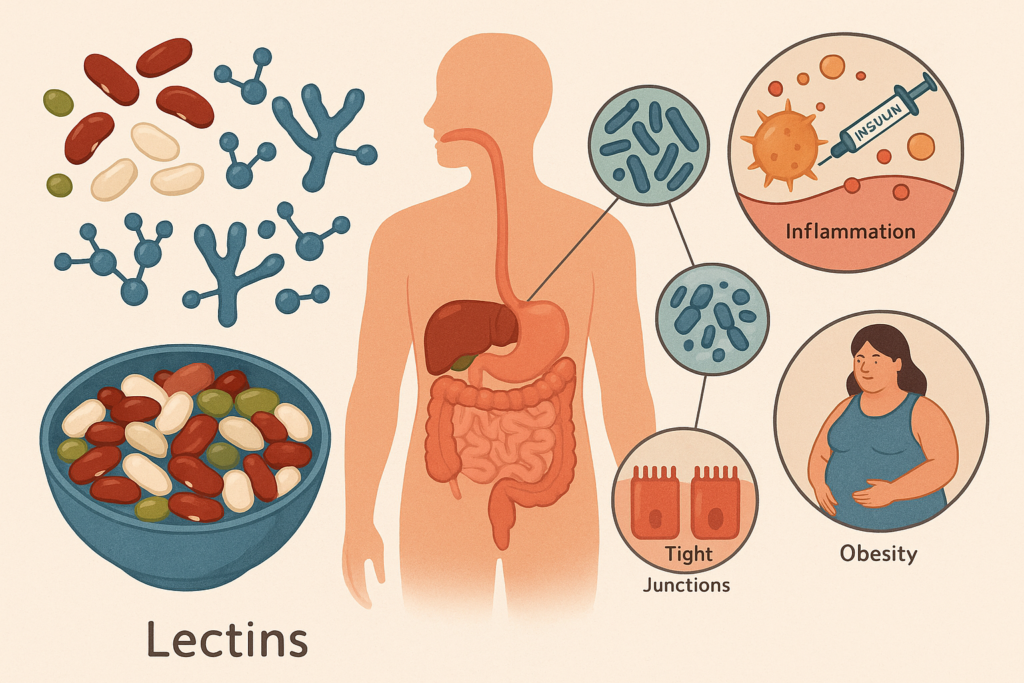

Modern nutrition research often circles back to a handful of food components that seem to spark endless debate like sugar, seed oils, gluten, processed additives, and more recently, lectins. These naturally occurring proteins, concentrated in certain plant foods, have attracted attention not only for their potential digestive effects but also for their possible role in metabolic health. Some people claim that lectins interfere with insulin signaling, disrupt nutrient absorption, or trigger inflammatory cascades that ultimately influence weight, energy regulation, and long-term metabolic resilience.

But how strong is this connection? And more importantly, what does the science actually say about lectins and metabolic function?

This article takes a balanced, research-minded look at what we currently know, and what remains uncertain, about whether lectins may play a meaningful role in metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, obesity, and related conditions.

Understanding Lectins: Nature’s Binding Proteins

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins found in nearly all plants. Their biological role is surprisingly elegant: they help plants defend themselves against predators, pests, and pathogens by binding to cell membranes and interfering with digestive enzymes in would-be predators.

For humans, this means that certain lectins have the potential to interact with the lining of the digestive tract and, under the right conditions, influence nutrient absorption, gut permeability, and the gut microbiome. Most lectin-containing foods are completely safe once prepared properly. Pressure cooking, soaking, fermenting, and sprouting all dramatically reduce active lectin levels.

However, when lectins remain intact or are consumed in large amounts by individuals who are already metabolically sensitive, their physiological effects become more relevant.

Metabolic Health: A System That Lives in the Gut as Much as in the Bloodstream

Before diving into lectins specifically, it’s useful to understand that metabolic health is not just about blood sugar. It’s an intricate dance involving:

- Insulin sensitivity

- Inflammation and immune signaling

- Gut barrier integrity

- Microbiome balance

- Hormonal responses to food

- Energy utilization and storage

Anything that influences these pathways, positively or negatively, has the potential to alter long-term metabolic function. Because lectins interact with the gut lining and immune system, researchers have started asking whether these proteins might indirectly influence metabolic states.

The Theories Linking Lectins to Metabolic Issues

While research is still emerging, several theoretical pathways have been proposed by scientists exploring lectins’ possible metabolic effects. These theories are rooted in known physiological mechanisms rather than speculation.

1. Lectins May Influence Gut Permeability

Some lectins, particularly those found in grains, beans, and nightshades, have demonstrated the ability in laboratory settings to bind to intestinal cells and alter the tight junctions that keep the gut barrier intact. This does not occur universally in humans, but the potential exists, especially when foods are undercooked.

A compromised gut lining can allow microbial fragments, undigested proteins, and immune-activating compounds to enter the bloodstream. This phenomenon, sometimes described as “metabolic endotoxemia,” has been linked to:

- chronic, low-grade inflammation

- insulin resistance

- increased fat storage

- disturbed appetite regulation

If a person is genetically susceptible or already inflamed, lectin-driven permeability changes could amplify metabolic challenges.

2. Lectins Can Interact With Insulin Receptors, At Least in Theory

In older biochemical research, certain plant lectins, like those from raw kidney beans or wheat germ, were shown to bind to insulin receptors or insulin-like molecules. In the laboratory, this sometimes produced an insulin-mimicking effect or interfered with normal insulin signaling.

This does not mean eating lectin-containing foods causes diabetes. It does, however, raise the question of whether lectin exposure in sensitive individuals could alter:

- post-meal glucose response

- insulin sensitivity

- pancreatic workload

There is no conclusive human trial proving that dietary lectins directly cause metabolic disease. But the possibility that they may influence insulin-related pathways in certain individuals remains open for exploration.

3. Lectins May Trigger Low-Grade Inflammation

Inflammation is one of the root drivers of metabolic dysfunction. Some lectins, when consumed in large quantities or in underprepared foods, have been shown to activate immune cells in the gut. This can stimulate the release of inflammatory cytokines, which circulate through the bloodstream and influence metabolic signaling.

Chronic exposure to inflammatory triggers, dietary or otherwise, can lead to:

- impaired glucose tolerance

- increased cortisol levels

- weight gain and fluid retention

- mitochondrial stress

- difficulty burning stored fat

For people already on the metabolic edge, even small inflammatory nudges from food can matter.

4. Lectin Sensitivity May Exacerbate Existing Metabolic Disorders

Not everyone reacts to lectins in the same way. Most people process them without any notable symptoms. However, in individuals with:

- autoimmune disorders

- irritable bowel syndrome

- gut dysbiosis

- diabetes or prediabetes

- chronic inflammatory conditions

Lectins may act as amplifiers.

In metabolic disorders, especially insulin resistance and obesity, the immune system is often already dysregulated. The gut barrier is often compromised. The microbiome is frequently altered. In this context, lectins may have a disproportionately strong impact compared to someone who is otherwise metabolically resilient.

What the Research Actually Shows (and Doesn’t Show Yet)

It’s important to separate speculation from scientific evidence. Here’s the current state of research:

✔ Strong Evidence: Lectins Affect the Gut Lining in Laboratory Studies

Cell and animal models consistently show that certain lectins can bind to intestinal cells and alter permeability. These changes are most pronounced with:

- raw kidney bean lectins

- wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)

- some peanut lectins

In humans, these effects are rarely measured directly, but they likely mirror what has been seen in controlled environments, especially with improper food preparation.

✔ Moderate Evidence: Lectins Influence Immune Activation

Several studies demonstrate that lectins can activate immune receptors and stimulate cytokine release. Since the gut’s immune network plays a major role in systemic inflammation, this is a plausible mechanism linking lectins to metabolic signaling.

✔ Suggestive, Not Definitive Evidence: Lectins Affect Insulin and Glucose Regulation

There are intriguing biochemical studies showing that specific lectins interact with insulin receptors, mimic insulin, or interfere with carbohydrate metabolism. However:

- human trials are extremely limited

- effects vary dramatically depending on the type of lectin

- properly cooked foods usually deactivate lectins

Still, the possibility remains that lectins contribute to metabolic irregularities for certain individuals.

✔ Limited but Emerging Evidence: Low-Lectin Diets Improve Metabolic Markers in Some People

Anecdotal reports and small-scale clinical observations have noted improvements in:

- fasting glucose

- waist circumference

- inflammatory markers

- digestive discomfort

- energy levels

when participants follow a low-lectin diet. These improvements could stem from several factors, not only lectin reduction but also removal of ultra-processed foods, increased vegetable intake, or higher protein consumption.

Still, the pattern is difficult to ignore.

✘ No Evidence: Lectins Alone Cause Metabolic Disease

There is no scientific basis for the idea that lectins:

- directly cause diabetes

- independently create obesity

- trigger metabolic syndrome in healthy individuals

Lectins are one piece of a much larger puzzle. For some people, they may be a meaningful trigger. For others, they’re insignificant.

How Cooking Reduces Lectins and Why That Matters for Metabolism

Many concerns about lectins surround raw or undercooked foods. In reality, traditional cooking methods significantly reduce lectin activity:

Pressure Cooking

Perhaps the most powerful method. It reliably destroys lectins in beans, lentils, and many grains. Properly pressure-cooked legumes are far less likely to trigger metabolic or inflammatory responses.

Boiling – Sustained boiling for enough time (not a quick simmer) inactivates most harmful lectins.

Soaking + Rinsing – Helps remove some lectins and reduces the cooking time needed to deactivate the rest.

Fermentation & Sprouting – Transform lectins by breaking down their structure and reducing their ability to bind to gut cells. This is one reason fermented foods have such a long global history. They improve digestibility and nutrient availability.

When foods are prepared properly, lectins often become far less significant metabolically.

The Gut Microbiome Connection: Where Lectins May Have the Most Influence

One of the most compelling areas of research is the interaction between lectins and the microbiome. Some lectins appear to:

- reduce beneficial bacteria

- encourage bacterial overgrowth

- bind to microbial cell walls

- alter the balance of short-chain fatty acids

The microbiome is deeply connected to metabolic health. It influences appetite hormones, inflammation, nutrient metabolism, and immune response. If lectins disrupt microbiome balance in sensitive individuals, metabolic changes may follow.

This is an area where future research is likely to clarify many unanswered questions.

Why Some People Thrive on High-Lectin Diets While Others Struggle

This discrepancy often confuses people: why do some individuals eat beans, tomatoes, lentils, quinoa, peanuts, and wheat with excellent health outcomes, while others experience inflammation, weight gain, fatigue, or digestive distress?

Several factors explain this:

Genetics – Some individuals have more robust gut linings or different carbohydrate-binding receptors that make them less reactive to lectins.

Microbiome Strength – A diverse, balanced microbiome can neutralize many dietary stressors.

Gut Permeability – If the gut barrier is already compromised, lectins may cause outsized trouble.

Existing Inflammation – The more inflamed a person is, the more sensitive they become to otherwise harmless compounds.

Food Preparation Differences – Traditional cultures rarely ate lectin-rich foods without soaking, sprouting, fermenting, or cooking them thoroughly.

Does This Mean Everyone Should Avoid Lectins? Not Necessarily.

Lectins are not universally harmful. For metabolically healthy individuals, properly prepared lectin-containing foods, especially legumes, are often associated with better health outcomes, not worse.

However, for people experiencing:

- chronic inflammation

- bloating or digestive symptoms

- autoimmune issues

- insulin resistance or unstable blood sugar

- obesity or stubborn weight gain

lectins may be an overlooked factor worth experimenting with.

A temporary low-lectin trial often provides clarity. Many people discover that reducing high-lectin foods decreases symptoms and stabilizes energy and metabolic markers. Others find no difference at all and that is equally valuable information.

A Practical, Scientific Approach to Lectins and Metabolism

If you’re curious about whether lectins influence your metabolic health, consider the following strategy:

1. Track Your Symptoms

Use your “Tracking Low-Lectin” or “Maintaining Low-Lectin” journals to document:

- blood sugar responses

- bloating

- cravings

- fatigue

- inflammation flare-ups

- brain fog

- weight fluctuations

Consistent patterns often reveal more than theory.

2. Try a 30-Day Low-Lectin Reset

This can help you establish a baseline. If symptoms improve, lectins may be playing a role.

3. Reintroduce Foods Systematically

Bring back one food at a time, pressure-cooked beans, tomatoes, peppers, quinoa, lentils, and observe any changes.

4. Prioritize Cooking Methods

If lectins bother you, avoid:

- slow cookers for beans

- undercooked legumes

- raw wheat products (e.g., wheat germ)

and favor:

- pressure cooking

- fermentation

- sprouting

5. Support the Gut Lining

Include foods like:

- collagen or bone broth

- polyphenol-rich vegetables

- fermented foods

- soluble fiber (acacia, psyllium, pectin)

These help strengthen gut resilience.

The Bottom Line: A Nuanced but Meaningful Relationship

So, are lectins linked to metabolic issues? The most accurate answer is:

They can be, but not universally, and not always directly.

Lectins have well-documented effects on gut permeability, immune activation, and biochemical signaling pathways that influence metabolic function. In people who are already metabolically or immunologically sensitive, these effects may be amplified enough to matter.

For others, especially those who prepare foods traditionally, lectins may pose no problem at all.

What the science consistently shows is this:

- Lectins are powerful, biologically active compounds.

- Sensitivity varies widely.

- Gut health plays a central role.

- Cooking and preparation methods make an enormous difference.

- Metabolic issues are multi-layered, and lectins are one factor among many.

If you’re seeking metabolic stability, improved energy, and fewer inflammatory swings, exploring a low-lectin approach is both reasonable and scientifically grounded, especially when paired with thoughtful food preparation and structured tracking.