The moment food enters the body, a series of microscopic exchanges quietly begins. Most of these interactions are harmless and routine, fueling the body with nutrients that pass through cells without incident. Yet some naturally occurring plant compounds behave differently. Among them are lectins, a diverse family of carbohydrate binding proteins that exhibit a unique ability to attach themselves to cell surfaces. To understand why some people feel sensitive to high lectin foods, it helps to step beyond the bigger picture and look at what unfolds at the cellular level. The gut lining is not a simple wall but an active, living interface made of specialized structures, receptors, and immune signaling pathways. Lectins move through this environment in distinctive ways, sometimes creating friction, sometimes passing unnoticed, depending on context, concentration, and personal physiology.

This cellular perspective does not paint lectins as universally harmful. They are structurally complex proteins that plants use for defense and signaling. Humans encounter them daily in foods like legumes, grains, nightshades, and seeds. Many lectins pass through the digestive system without causing issues, especially when foods are properly cooked or pressure cooked. Still, some individuals appear more responsive to specific lectins, which has ignited interest in understanding exactly what occurs at the gut lining when lectins make contact.

The Gut Lining as a Living Barrier

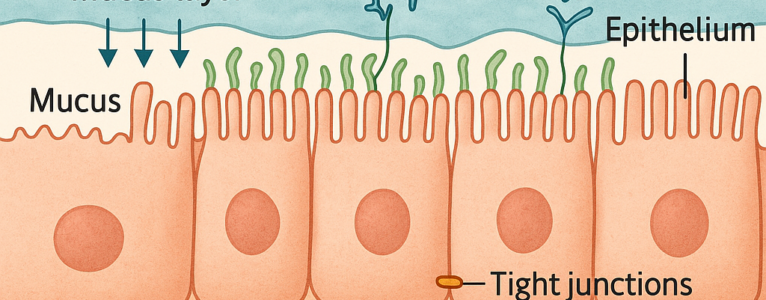

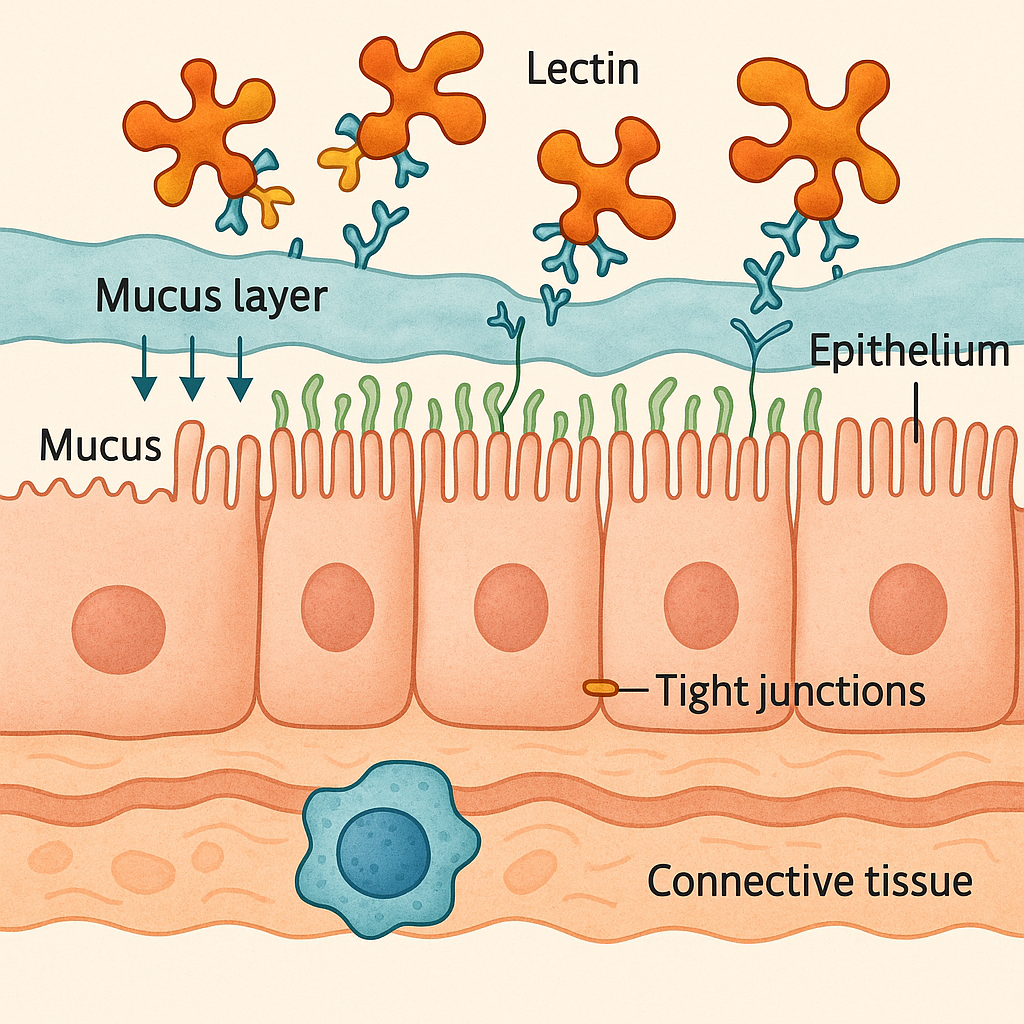

To appreciate lectin interactions, it helps to understand the structure of the gut lining. Far from being an inert tube, the intestinal wall is one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body. It is only a single layer of epithelial cells thick, arranged side by side in tight formation. These cells renew themselves rapidly, with a full turnover occurring every few days. They are supported from below by connective tissue and immune cells and topped by a protective mucus layer that acts like a buffer between the gut contents and the cell surfaces.

Each epithelial cell is fitted with microvilli, tiny projections that increase the available surface area. These microvilli are coated with a glycocalyx, which is a dense layer of carbohydrates attached to proteins and lipids. This structure is important because lectins are drawn to carbohydrate patterns, and the glycocalyx is rich with them. The intestinal surface is therefore naturally abundant in docking points, not because the body wants lectins to bind, but because this carbohydrate coating is essential for digestion, cell protection, and nutrient absorption.

The gut lining also contains tight junctions, which are protein complexes that act as seals between neighboring cells. They regulate the flow of substances passing between the cells rather than through them. A healthy gut maintains tight control over what can cross this barrier, but this control is dynamic. It can be loosened or tightened in response to hormones, nutrients, stress signals, and inflammatory conditions. This variability means that lectins encounter a changing landscape. Sometimes the barrier is robust and resistant. Other times it is more vulnerable.

Binding: The First Point of Interaction

Lectins have a specific signature. They attach themselves to carbohydrate structures, often preferring particular shapes such as mannose, galactose, or complex sugar chains. When lectins reach the small intestine, they encounter the glycocalyx covering the microvilli. For many lectins, this surface contact is as far as the interaction goes. They bind temporarily, remain on the exterior of the gut lining, and eventually detach and are eliminated with waste.

However, some lectins have stronger affinities or exhibit higher resistance to digestive enzymes. In these cases, binding becomes the starting point for downstream effects. When a lectin binds to the glycocalyx, it may cluster receptors on the cell surface. This clustering can trigger changes in signaling pathways inside the epithelial cells. The cells interpret surface clustering as a message, even if it is not one the body expects or wants.

Some lectins are also capable of resisting heat or acidic conditions, which means they reach the intestine intact enough to preserve their binding ability. Undercooked legumes are a classic example. Certain bean lectins lose their activity entirely when properly boiled or pressure cooked but remain potent when cooked at too low a temperature. This explains why improperly prepared red kidney beans can cause intense gastrointestinal distress due to lectin activity.

Lectin Influence on the Mucus Layer

The mucus layer is an often overlooked but crucial feature of gut defense. It creates a physical buffer that prevents direct contact between many dietary components and the epithelial cells. The mucus is constantly renewed. This renewal slows down external binding and acts as a protective shield.

Some lectins, particularly those with strong affinity for mucin carbohydrates, can embed themselves within the mucus. This does not necessarily damage the layer, but it may alter how quickly mucus is shed or how easily enzymes reach the underlying carbohydrates. In sensitive individuals, this interaction may be enough to create mild irritation or increase the workload on cells responsible for mucus production.

In experimental conditions, certain lectins have been shown to thin the mucus layer or alter its physical structure. This has been observed primarily in controlled laboratory settings using concentrated lectin solutions rather than whole foods at normal dietary levels. Still, the findings provide insight into how lectins might influence the gut environment if present in large quantities or if the mucus layer is already compromised.

Effects on Tight Junction Regulation

Perhaps the most discussed cellular effect of lectins involves tight junctions. These protein complexes regulate permeability. They allow water, ions, and small nutrients to pass while restricting larger or potentially harmful molecules.

Some lectins, especially those derived from grains or certain legumes, appear capable of affecting signaling pathways that influence tight junction proteins. When lectins bind to the epithelial surface, they may activate intracellular messengers that alter how tightly these proteins hold together. In models where tight junctions loosen, the gut becomes more permeable. This heightened permeability is often referred to as increased intestinal permeability. Increased permeability does not automatically mean disease, but it can contribute to immune system activation or discomfort.

Much of the research on this mechanism has come from laboratory and animal models. Human data remains mixed and continues to be debated. Some individuals may be more genetically predisposed to permeability shifts. For them, dietary lectins may have a more noticeable effect. Others maintain strong junction integrity regardless of lectin exposure.

Cooking methods play a major role in moderating these effects. Heat sensitive lectins lose their ability to influence tight junctions once denatured. Proper cooking, fermentation, sprouting, and pressure cooking reduce lectin activity and help minimize these interactions.

Interaction With Immune Cells in the Gut Wall

Beneath the epithelial layer lies a network of immune cells constantly monitoring the gut lumen. They are unable to reach into the intestinal space, but they communicate with epithelial cells and respond to signals that pass through the barrier.

If lectins disrupt the surface environment, immune cells may detect changes in cytokine patterns or receptor expressions. Epithelial cells can send distress signals if binding events trigger unusual intracellular pathways. This does not mean that lectins directly inflame the immune system. Instead, the response depends heavily on the individual and the context. Some lectins are capable of stimulating immune cells in controlled laboratory experiments, but real-life exposure through cooked food is typically far less concentrated.

Still, for individuals who already have a primed immune environment, such as those with inflammatory bowel conditions or compromised gut integrity, lectins may add an additional layer of stimulation. This may appear as bloating, discomfort, or fatigue after consuming high lectin meals. Again, preparation methods significantly reduce this risk by denaturing the proteins that bind most aggressively.

How the Body Handles Lectins That Pass Through

Most lectins do not cross the gut lining. Those that do are usually transported through normal cellular processes such as endocytosis, where small particles are taken in by cells and then neutralized. Some lectins are passed through the body intact but do not accumulate in tissue. Instead, they are carried out through waste or processed by the liver.

The speed at which the gut lining turns over also limits long-term lectin effects. Even if lectins bind strongly to cell surfaces, the epithelial cells themselves are replaced within days. This rapid regeneration helps buffer the body from prolonged exposure.

However, the transient period during which lectins are attached may still influence cellular signaling. This is why some people experience short-term symptoms after eating high lectin foods and feel relief when those foods are removed or prepared differently.

Personal Variation in Lectin Sensitivity

Perhaps the most important factor in lectin and gut interactions is the individual. Some people have robust digestive enzyme activity that breaks down a large portion of lectins before they reach the intestine. Others have thicker mucus layers or tighter junctions that reduce lectin binding opportunities. Genetics, stress levels, sleep, microbiome composition, and past health conditions all influence how the gut lining responds.

The microbiome in particular plays a significant role. Certain beneficial bacteria help digest lectin containing foods or reduce lectin binding by modifying carbohydrate structures in the gut. Individuals with diverse, healthy microbiomes often tolerate lectins better because their microbes essentially help do part of the processing. Those with disrupted microbiomes may struggle with foods they once tolerated without issue.

This explains why two people can eat the same lectin rich meal and have completely different experiences. Diet personalization becomes essential when navigating these complex cellular interactions.

What Research Still Does Not Fully Understand

Despite decades of study, lectins continue to puzzle researchers. Their behavior in isolated lab conditions does not always mirror their behavior in whole food meals. Lectins vary widely in structure, stability, and biological activity. Some have documented cellular effects. Others appear neutral. Many remain understudied.

The gut lining itself adds another layer of complexity because its permeability, mucus thickness, and epithelial turnover are constantly shifting. These shifts make it difficult to generalize how lectins behave in every person. More human studies are needed to clarify dose effects, preparation methods, and interactions with specific microbiome profiles.

What is clear is that lectins are biologically active proteins. They are not inherently toxic, but they interact with the gut lining in ways that can matter for certain individuals. Their cellular effects are real but highly dependent on concentration and context.

Practical Takeaways From a Cellular Perspective

Focusing on cellular interactions provides a balanced lens. It becomes easier to understand why some people benefit from lowering lectins, why others eat them without issue, and why preparation techniques matter.

Lectins bind to carbohydrates on the intestinal surface and can influence epithelial signaling. Some lectins affect mucus consistency or tight junction regulation in laboratory conditions. Cooking methods that denature lectins significantly reduce their activity. The health of the mucus layer, gut wall integrity, and microbiome diversity all influence how an individual responds.

These details do not require anyone to fear lectins. Instead, they encourage a mindful approach. Observing how your body responds, preparing foods properly, and paying attention to digestive changes help you personalize your diet in ways that support long-term comfort and health.