Autoimmune conditions are often described as if they all belong to the same family, sharing a single cause and a single solution. In reality, they behave more like distant relatives who share a surname but live very different lives. One person may experience joint pain that flares after certain meals. Another struggles with digestive distress, brain fog, or skin reactions that seem to appear without warning. When people begin exploring dietary triggers, lectins often enter the conversation, sometimes as a suspected culprit, sometimes as a confusing footnote.

What makes lectins particularly controversial is that their effects are not uniform. Some people with autoimmune conditions notice clear improvement when lectins are reduced, while others see modest changes or none at all. This uneven response raises an important question: why do lectins appear to affect some autoimmune conditions more strongly than others?

The answer lies in the intersection of immune system behavior, gut integrity, genetics, and the way lectins interact with specific tissues in the body. Lectins are not inherently toxic substances, but they are biologically active proteins with the ability to bind to carbohydrates on cell surfaces. That binding behavior gives them influence, and in the context of an immune system already prone to misfiring, influence matters.

Lectins and the Immune System’s Tipping Point

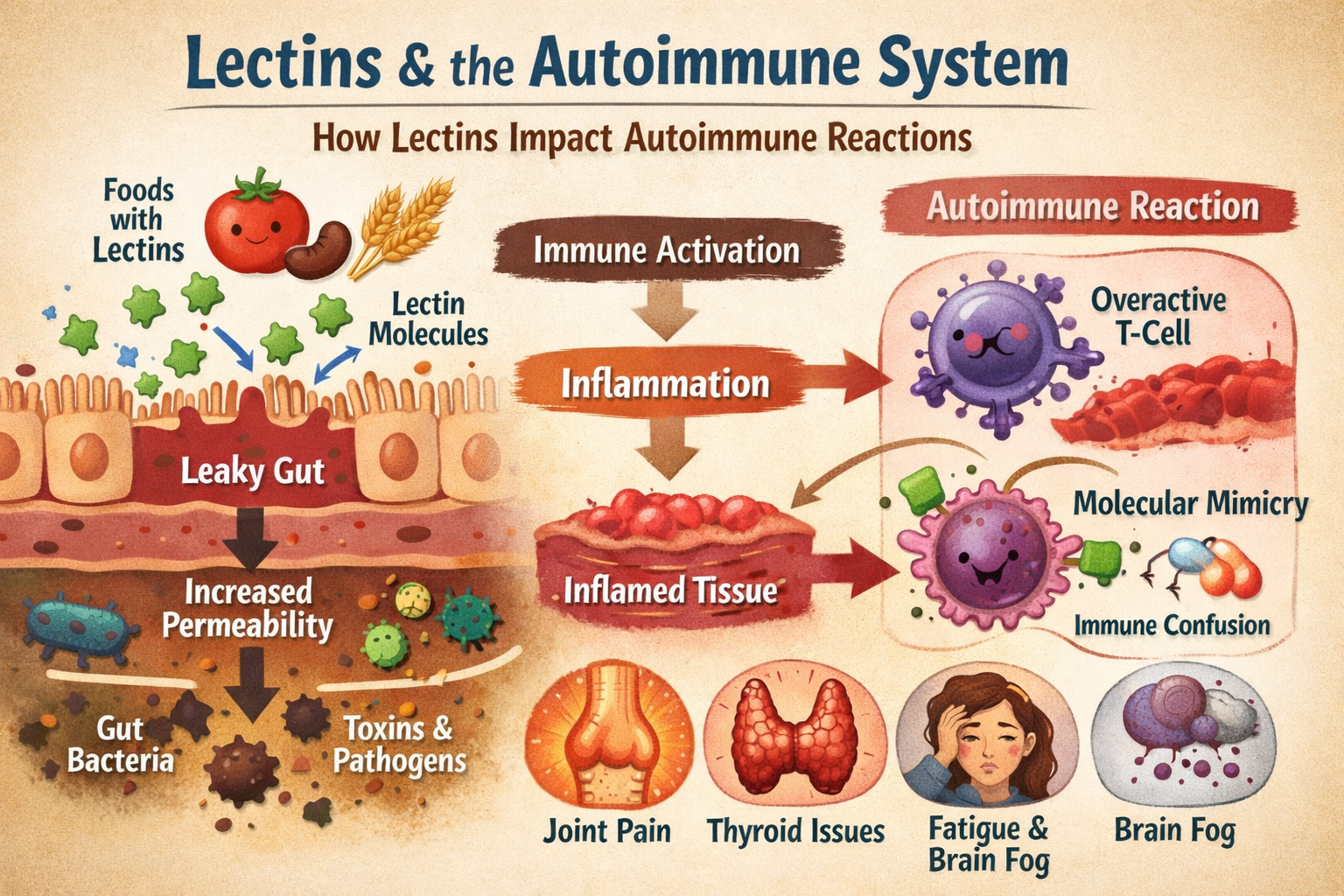

Lectins evolved as part of a plant’s defense strategy. By binding to carbohydrates, they can interfere with digestion in insects and animals that consume them, discouraging predation. In humans, most lectins are partially neutralized through cooking, soaking, fermentation, or digestion. However, not all lectins are rendered inactive, and some retain the ability to interact with cells lining the gut.

For people without immune dysregulation, these interactions are usually harmless. The immune system recognizes lectins as foreign proteins, responds appropriately, and moves on. In autoimmune conditions, the immune system is already operating with heightened sensitivity. It may react more aggressively to stimuli that would otherwise be ignored.

This does not mean lectins cause autoimmune disease. Rather, they can act as amplifiers. In a system already primed for inflammation, additional immune triggers may increase the likelihood of flare-ups or symptom persistence. The degree of that amplification depends on where the immune system is most vulnerable.

Gut Barrier Integrity as a Key Divider

One of the strongest predictors of lectin sensitivity in autoimmune conditions appears to be gut barrier integrity. The intestinal lining acts as a selectively permeable barrier, allowing nutrients to pass while keeping larger proteins and microbes at bay. When this barrier is compromised, a condition often referred to as increased intestinal permeability, immune exposure changes dramatically.

Some autoimmune conditions are strongly associated with gut barrier dysfunction. In these cases, lectins that survive digestion have a greater opportunity to interact with immune cells beneath the intestinal lining. This exposure can stimulate inflammatory pathways, increase cytokine signaling, and reinforce immune vigilance.

Other autoimmune conditions may originate or primarily operate in tissues less directly connected to the gut. In these cases, lectins may play a smaller role, or their impact may be indirect rather than central. The immune system still responds to lectins, but the response may not translate into noticeable symptom changes.

This distinction helps explain why dietary changes targeting lectins can feel transformative for some people and subtle for others.

Tissue Targeting and Molecular Mimicry

Another reason lectins affect autoimmune conditions unevenly involves molecular mimicry. Some lectins bind to carbohydrate structures that resemble those found in human tissues. When immune cells react to lectin-bound structures, they may inadvertently increase surveillance or reactivity toward similar structures in the body.

If an autoimmune condition targets tissues with carbohydrate patterns that resemble those lectins interact with, the immune response may intensify. Joint tissues, nervous tissue, skin, and the thyroid all have unique carbohydrate profiles. The overlap between lectin binding preferences and tissue vulnerability varies.

This does not mean lectins directly attack specific organs. Instead, they can contribute to immune confusion in systems already struggling to distinguish self from non-self. In conditions where molecular mimicry is already suspected to play a role, lectins may add another layer of complexity.

Genetics and Immune Programming

Genetic variability further explains why lectins affect people differently. Genes influence everything from digestive enzyme production to immune receptor sensitivity. Certain genetic profiles may lead to slower lectin breakdown, stronger immune recognition, or increased inflammatory signaling.

Human leukocyte antigen, or HLA, variations are particularly relevant in autoimmune disease. These molecules help present antigens to immune cells. Differences in HLA structure influence which proteins are flagged as threats and how aggressively the immune system responds.

For some individuals, lectins may be presented to immune cells in a way that promotes tolerance. For others, the same lectins may be presented as high-priority threats. The food itself has not changed, but the immune interpretation has.

This genetic lens helps move the conversation away from universal dietary rules and toward personalized strategies.

The Role of the Microbiome

The gut microbiome acts as an intermediary between lectins and the immune system. Certain microbes can degrade lectins, reducing their activity before they interact with human tissues. Others may bind lectins themselves, altering microbial balance and immune signaling.

Autoimmune conditions are often associated with altered microbiome composition. When beneficial microbes are reduced and opportunistic species dominate, lectin processing may become less efficient. This can increase immune exposure and inflammation.

Interestingly, microbiome composition can change over time. Stress, antibiotics, illness, sleep patterns, and diet all shape microbial populations. This means lectin sensitivity is not necessarily permanent. As the microbiome stabilizes, tolerance may improve.

This dynamic nature explains why some people notice worsening symptoms early in a dietary shift before gradual improvement occurs.

Why Some Autoimmune Conditions Respond More Clearly

Autoimmune conditions that involve the gut, connective tissue, or widespread systemic inflammation often show the clearest responses to lectin reduction. This is not because lectins are uniquely harmful, but because they interact more directly with the pathways already involved.

Conditions with localized immune targets or strong genetic drivers may show less dramatic changes. In these cases, lectin reduction may still support overall immune balance, but it is unlikely to be a standalone solution.

This distinction matters. When people expect identical outcomes across different autoimmune conditions, disappointment follows. Understanding that lectins influence immune environments rather than acting as direct causes allows for more realistic expectations.

The Importance of Preparation and Context

How lectins are consumed matters as much as whether they are consumed. Traditional food preparation methods evolved for a reason. Soaking, fermenting, sprouting, and pressure cooking significantly reduce lectin activity in many foods. In cultures where these practices remain common, lectin exposure is often lower despite high consumption of legumes or grains.

Modern food systems prioritize speed and convenience. Highly processed foods may retain lectin activity while lacking the fibers and micronutrients that support gut health. In this context, lectins can have a different impact than they would in traditionally prepared foods.

For individuals with autoimmune conditions, context is critical. Removing lectins entirely may not be necessary or sustainable. Reducing high-lectin foods while improving preparation methods can often provide benefits without excessive restriction.

Moving Away from Fear and Toward Understanding

One of the challenges in lectin discussions is the tendency toward fear-based narratives. Lectins are sometimes portrayed as poisons lurking in everyday foods. This framing oversimplifies the science and creates unnecessary anxiety.

Lectins are better understood as biologically active compounds that interact with the immune system. In some bodies, those interactions matter more. In others, they barely register. The goal is not to eliminate lectins universally, but to understand their role within an individual immune landscape.

This perspective aligns with a broader shift in nutritional science toward personalization. Instead of asking whether lectins are good or bad, the more useful question becomes how lectins interact with a specific body at a specific point in time.

Listening to Patterns Rather Than Labels

Autoimmune diagnoses provide useful information, but they do not capture the full picture. Two people with the same diagnosis may have entirely different triggers and responses. Symptom patterns, digestive feedback, energy levels, and inflammatory markers often reveal more than labels alone.

When people experiment with lectin reduction thoughtfully, patterns emerge. Some notice rapid improvement in joint stiffness or digestive comfort. Others see changes in energy or mental clarity. Some experience no noticeable difference and benefit more from other interventions.

None of these outcomes are failures. They are data points.

A Tool, Not a Doctrine

Lectin awareness works best when treated as a tool rather than a doctrine. It offers a framework for understanding why certain foods provoke reactions and how preparation methods influence immune exposure. It does not demand rigid adherence or universal exclusion.

For people navigating autoimmune conditions, this flexibility is essential. Stress itself is a powerful immune modulator. Diets that create fear or social isolation can undermine the very healing they aim to support.

The most sustainable approach is one rooted in curiosity. What happens when certain foods are removed temporarily? What changes when they are reintroduced in different forms? How does sleep, movement, and stress management interact with dietary changes?

Why the Differences Matter

Understanding why lectins affect some autoimmune conditions more than others helps shift the conversation from blame to biology. It acknowledges complexity without surrendering agency. It allows people to experiment intelligently rather than blindly following rules.

Lectins are not villains, nor are they irrelevant. They occupy a nuanced middle ground where context, preparation, genetics, and immune health determine impact. For some, adjusting lectin intake becomes a turning point. For others, it is one piece of a much larger puzzle.

Living low-lectin is not about perfection. It is about learning how the body responds and responding with intention. When that mindset replaces fear, lectin awareness becomes less about restriction and more about resilience.