Lectins have become one of the most debated compounds in modern nutrition. Some people say lectins are harmless in small amounts and easily neutralized by cooking. Others argue that they can irritate the digestive system, increase inflammation, and contribute to long-term health issues, especially for individuals who already struggle with gut sensitivity, autoimmune symptoms, or metabolic problems. As with most things in nutrition science, the truth is nuanced and sits somewhere in the middle.

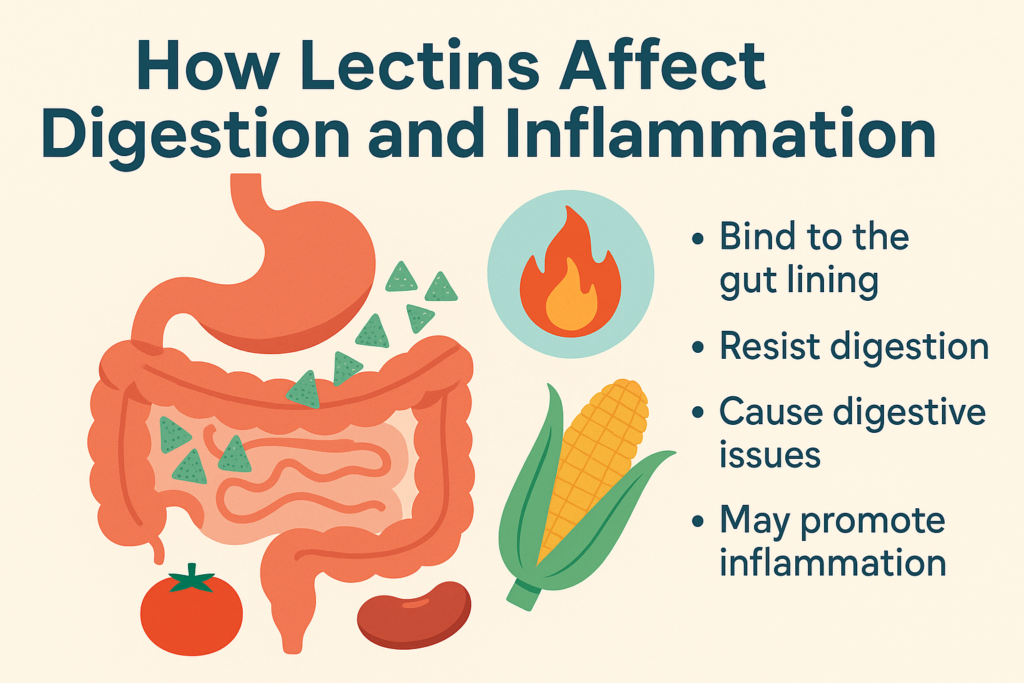

What is becoming clear, however, is that lectins interact with the gut in uniquely powerful ways. They bind to carbohydrates, stick to cell membranes, and often survive digestion. For some people, this is barely noticeable. For others, these properties may contribute to digestive discomfort, bloating, nutrient malabsorption, and chronic inflammation.

This article breaks down what we actually know so far based on current research, biochemical understanding, and emerging clinical perspectives while avoiding hype and focusing on what matters for your health.

What Are Lectins, Exactly?

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins found in many plants, especially seeds, beans, grains, and the skins of certain vegetables. Plants use lectins as part of their natural defense system. Because plants can’t run from predators, they evolved chemical strategies like lectins, tannins, oxalates, and phytates to discourage being eaten.

Lectins are unique because they bind strongly to sugars on the surface of cells. In humans, our digestive tract is lined with glycoproteins (proteins coated with sugars), which means lectins can sometimes attach themselves to the gut wall. Depending on the type of lectin and the amount consumed, this binding may:

- Irritate the intestinal lining

- Interfere with nutrient absorption

- Activate immune responses

- Affect the balance of gut bacteria

Not all lectins act the same way. Some are mild. Some are neutral. A few, like the infamous ricin from castor beans, are dangerously toxic, though these never appear in food sources used by the public.

Many food-based lectins are greatly reduced or neutralized through traditional cooking methods, which is why preparation matters.

Why Lectins Can Be Difficult to Digest

Humans lack the enzymes to break lectins down efficiently. Unlike carbohydrates, proteins, or fats, lectins resist digestion and often pass through the stomach and small intestine intact. Their resistance is partly due to their strong folding structure, which protects them from heat and digestive enzymes unless they’re cooked or processed correctly.

When lectins remain intact, they may:

1. Interact Directly with the Gut Lining

Lectins bind to carbohydrates on the surface of epithelial cells, the cells that form our gut barrier. This means they can “stick” to the intestinal wall, sometimes irritating it or altering the tight junctions that keep the gut barrier stable. This doesn’t automatically cause disease. But in sensitive individuals, especially those with existing gut permeability issues, lectins can add to the irritation.

2. Interfere With Nutrient Uptake

Some lectins bind to vitamins or minerals, reducing absorption. Others bind to enzymes involved in digestion, temporarily inhibiting them. This is one reason undercooked legumes cause discomfort. They still contain active lectins and enzyme inhibitors.

3. Trigger Immune Responses

Because lectins resist breakdown, the immune system may perceive them as foreign intruders. This can lead to low-grade inflammation as the body tries to neutralize or escort the lectins out. For most people, this isn’t a major problem. But for individuals prone to inflammatory flare-ups, even small triggers can make a noticeable difference in symptoms.

Lectins and Digestive Discomfort: What the Research Suggests

Lectins can contribute to digestive symptoms in several ways. While not everyone reacts, those who do often report:

- Bloating

- Gas

- Cramping

- Changes in bowel habits

- Fatigue after meals

- Joint stiffness

These symptoms often overlap with common gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS, SIBO, or dysbiosis. Lectins are not necessarily the cause of these issues, but they may worsen them due to the way lectins interact with gut cells and gut bacteria.

Lectins and the Gut Barrier

Researchers studying intestinal permeability, the often-referenced “leaky gut”, have found that certain lectins can affect tight junctions, the microscopic structures that keep intestinal cells sealed tightly together. When tight junctions loosen, particles that should remain inside the gut can escape into the bloodstream.

For some individuals, this increased antigen exposure leads to inflammation or immune activation.

Lectins and Gut Microbes

Some lectins have antimicrobial actions. This can be good or bad depending on the context:

- Positive effect: reducing harmful bacterial overgrowth

- Negative effect: disrupting beneficial microbes and gut balance

The gut microbiome is complex, and even subtle disruptions can change digestion, regularity, and inflammation.

Lectins and Inflammation: Digging Into the Mechanisms

Inflammation is part of the immune system’s response to perceived threats. When lectins bind to gut cells, the body sometimes interprets this as an irritant or foreign element. This can initiate inflammatory pathways.

Here are the main ways lectins may influence inflammation:

1. Immune Activation Through Gut Irritation

If lectins irritate or damage epithelial cells, immune cells may respond by releasing cytokines, chemical messengers involved in inflammation. Over time, if exposure continues and the gut lining remains irritated, this can contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation.

2. Altering the Intestinal Barrier

When lectins disrupt tight junctions, more antigens pass into the bloodstream. The immune system must work harder to identify and neutralize these elements. This increased immune burden can contribute to systemic inflammation.

3. Molecular Mimicry and Autoimmunity

Some researchers propose that lectins may play a role in autoimmune conditions through molecular mimicry, where the immune system mistakes the body’s own tissues for proteins similar to lectins. The science here is developing, and more research is needed, but individuals with autoimmune conditions often report symptom relief when lowering dietary lectin intake.

4. Blood Sugar and Insulin Responses

Certain lectins affect carbohydrate metabolism. Others may bind to insulin receptors. When combined with a high-starch diet, lectins may contribute to unstable blood sugar patterns in some people, an effect linked to inflammatory processes.

While none of these mechanisms prove that lectins cause disease, they do highlight why some people feel better when reducing them.

Why Some People Are More Sensitive Than Others

If lectins were universally problematic, everyone would experience digestive issues from lentils, tomatoes, kidney beans, and wheat. But clearly, they don’t. Sensitivity varies dramatically from person to person.

Factors that make someone more lectin-sensitive include:

• Pre-existing Gut Damage – Conditions that weaken the gut barrier; such as SIBO, IBS, celiac disease, or chronic stress, can increase lectin sensitivity.

• Autoimmune Disorders – People with autoimmune conditions often have heightened immune responses and may react strongly to lectin exposure.

• Genetic Variations – Differences in carbohydrate structures on gut cells may affect how lectins bind.

• Microbiome Composition – Certain beneficial bacteria appear to help break down or neutralize lectins. A disrupted microbiome may reduce this protective effect.

• Preparation Methods – Many lectin-rich foods become inflammatory only when:

- undercooked

- improperly soaked

- eaten raw

- processed in ways that preserve lectins

Traditional cooking often eliminates these problems, but modern shortcuts (e.g., slow cookers for beans) may leave more active lectins behind.

How Proper Preparation Reduces Lectins

The scariest stories about lectins usually involve improperly cooked kidney beans, which contain high levels of phytohemagglutinin. A raw or undercooked serving can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. Yet when fully cooked in boiling water or pressure-cooked, the lectin content drops dramatically.

Traditional cooking methods that reduce lectins include:

1. Soaking – Removing water-soluble lectins from beans, lentils, and some grains.

2. Pressure Cooking – One of the most effective ways to neutralize lectins, especially in legumes and tougher foods like potatoes.

3. Fermentation – Microbes break down lectins and improve digestibility. Fermented soy, for example, has significantly fewer lectins than raw or lightly processed soy.

4. Sprouting – Sprouting activates enzymes that reduce antinutrients and break down lectins.

5. Peeling and Deseeding – Many lectins reside in the skins and seeds of nightshades (tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers). Removing these parts can help lighten digestive load.

These practices are used around the world, long before anyone discussed lectins scientifically. Traditional cuisines figured out what worked simply because people felt better eating foods prepared this way.

Common High-Lectin Foods and How People React

Not all lectin-rich foods are equal. Here’s a simplified look at major categories:

Legumes – Beans, lentils, chickpeas, and peanuts are among the highest in lectins. For many people, these foods become well-tolerated after proper soaking and pressure cooking.

Grains – Wheat, barley, oats, and corn contain lectins, some of which are resistant to heat. Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) is particularly persistent. Some people experience bloating or joint stiffness after grain consumption.

Nightshades – Tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, and eggplant contain lectins primarily in skins and seeds. Individuals with autoimmune symptoms often report improvement after reducing nightshades.

Seeds and Certain Nuts – Lectins help protect seeds from predators. Many seeds are well tolerated, but some individuals notice reactions with cashews or pumpkin seeds.

Again, not everyone reacts. But those who do often experience dramatic improvements when adjusting intake.

What Emerging Research Tells Us and What It Doesn’t

Lectin research is still developing. We know enough to recognize that lectins affect digestion and inflammation, but not enough to establish universal dietary rules.

Here’s what we can say with confidence:

Supported by Research

- Lectins can irritate digestive tissue in sensitive individuals.

- Under-prepared legumes contain lectins that disrupt digestion.

- Lectins can interact with immune cells and inflammatory pathways.

- Certain lectins affect intestinal permeability in laboratory studies.

- Cooking, pressure cooking, fermenting, and sprouting reduce lectins significantly.

Still Uncertain

- Whether lectins independently cause autoimmune conditions

- Individual threshold levels for lectin tolerance

- Long-term health effects of moderate lectin intake

- Whether lectin sensitivity can be “healed” with gut repair protocols

- Ideal dietary guidelines for the general population

Because the science is evolving, most practitioners recommend personalized testing which may be trying a low-lectin diet for 2–4 weeks and observing changes. For many, this experiential approach provides much more clarity than theory alone.

How a Low-Lectin Approach Can Reduce Symptoms

People who reduce lectins often report improvements in:

- Bloating and digestive discomfort

- Joint pain

- Brain fog

- Fatigue

- Skin issues

- Weight fluctuations

- Food sensitivities

- Autoimmune flare-ups

The reason may be a combination of:

- Reduced irritation of the gut lining

- Lower inflammatory load

- Improved microbiome balance

- More stable blood sugar

- Better nutrient absorption

Even if lectins aren’t the only problem, lowering them may reduce overall stress on the system.

Who Might Benefit Most From Reducing Lectins

A low-lectin diet may be especially helpful for people with:

- IBS or digestive sensitivity

- Autoimmune conditions (RA, Hashimoto’s, psoriasis, lupus)

- Chronic inflammation

- Joint pain or unexplained swelling

- Fatigue after eating certain foods

- Sensitivity to beans, grains, or nightshades

- Difficulty regulating weight despite healthy habits

It does not require eliminating entire food groups, just modifying them, preparing them properly, or replacing problematic ingredients with low-lectin alternatives.

The Balanced Perspective: Lectins Aren’t the Enemy, But They Do Matter

Lectins are neither villains nor harmless. They exist on a spectrum, and their impact depends on the individual, the food source, and how the food is prepared.

The key takeaways:

- Lectins are biologically active proteins that can interact with the digestive and immune systems.

- Some people digest lectins easily; others experience significant symptoms.

- Proper preparation dramatically reduces lectin content in many foods.

- Eliminating or reducing lectins can offer relief for those with inflammation or gut sensitivity.

- More research is needed, but early evidence suggests lectins may influence inflammation in meaningful ways.

If you’ve struggled with digestive discomfort or unexplained inflammation, experimenting with a low-lectin lifestyle is a practical and low-risk approach to see how your body responds.

Final Thoughts

What we know so far about lectins is enough to take them seriously, especially for those who already deal with gut issues or chronic inflammation. Lectins are not universally harmful, but they can be biologically disruptive in certain contexts. The goal isn’t fear; it’s awareness. By understanding how lectins behave, how preparation changes them, and how your body responds, you gain the power to make informed decisions about your diet.

Listening to your body is still the most reliable tool you have. Science will continue to evolve, but your lived experience day by day and meal by meal, remains the clearest indicator of what fuels you best.