Sous-vide cooking has earned a reputation as one of the most precise and gentle ways to prepare food. Chefs praise it for producing perfectly cooked meat, vibrant vegetables, and repeatable results that are nearly impossible to mess up. Food is sealed in a bag, submerged in a temperature-controlled water bath, and held there long enough to reach an exact internal temperature. Nothing dries out. Nothing burns. Nutrients are said to be “locked in.”

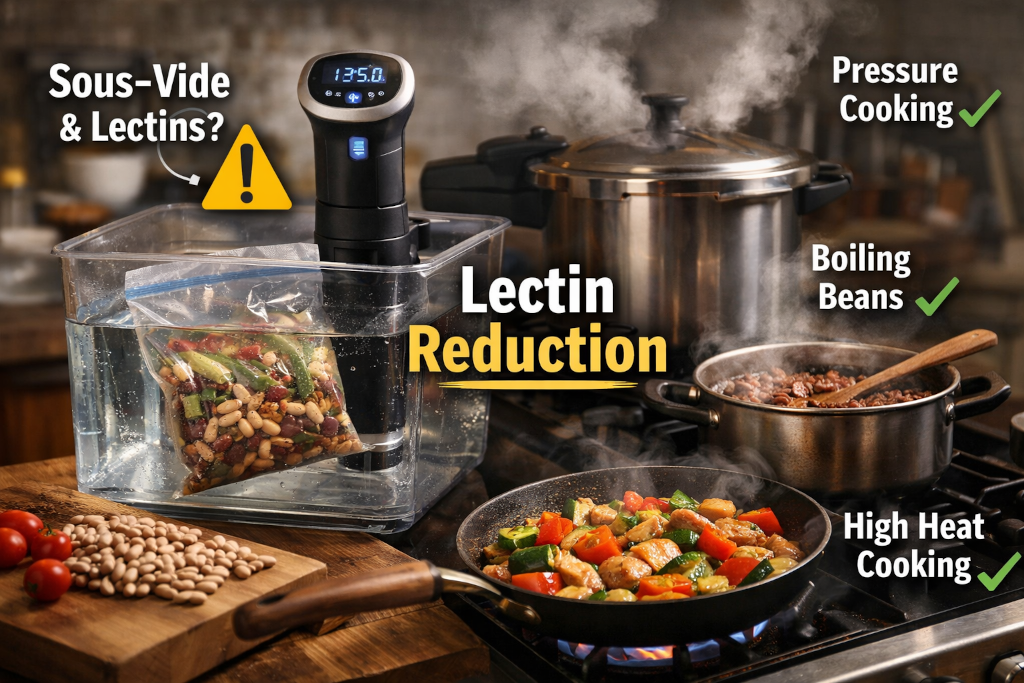

For many people, that sounds like the ideal way to cook. But when the goal is lectin reduction, sous-vide starts to look far less appealing.

This isn’t because sous-vide is unsafe or ineffective as a general cooking method. It’s because lectins behave very differently from bacteria, texture-related proteins, or delicate vitamins. Understanding why sous-vide struggles with lectins requires stepping away from culinary trends and looking more closely at how lectins are structured, how they survive digestion, and what actually disrupts them.

Lectins Are Not Fragile Proteins

Lectins are often described simply as “proteins,” but that label can be misleading. Many people assume that because proteins denature with heat, any cooking method should weaken lectins. In reality, lectins are remarkably resilient compared to many other plant proteins.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. Lectins exist as part of a plant’s defense system. Their job is not to nourish the organism that eats them, but to resist digestion, bind to tissues, and interfere with predators ranging from insects to mammals. Over time, plants that produced lectins capable of surviving harsh environments had an advantage.

As a result, many lectins tolerate:

- Acidic conditions similar to the stomach

- Digestive enzymes in the intestines

- Moderate heat exposure

This is why some lectins can pass through the digestive tract largely intact and still interact with the gut lining, immune cells, or microbiome. It’s also why cooking methods that are excellent for flavor or food safety are not automatically effective at reducing lectin activity.

What Actually Weakens Lectins

Research and practical observation consistently point to a few factors that meaningfully reduce lectin activity:

- High temperatures

- Sustained heat exposure

- Moist heat combined with pressure

- Extended boiling with water exchange

- Fermentation and enzymatic breakdown

What these methods share is not subtlety, but intensity. Lectins tend to resist gentle treatment and yield only when structural bonds are disrupted enough to interfere with their carbohydrate-binding ability.

This is where sous-vide runs into trouble.

Sous-Vide Is Designed to Be Gentle

Sous-vide excels precisely because it avoids extremes. Most sous-vide cooking happens between 120°F and 185°F (49–85°C), depending on the food. Even when vegetables are cooked sous-vide, temperatures rarely approach a rolling boil, let alone the higher effective temperatures achieved under pressure.

From a food safety perspective, this is fine. Pathogens can be controlled through time and temperature combinations. From a texture perspective, it’s excellent. But from a lectin-reduction perspective, it’s often insufficient.

Lectins don’t just need heat. They need disruptive heat. They are not easily “softened” into inactivity. Many retain their binding properties unless exposed to temperatures high enough, long enough, and often under conditions that physically alter their structure.

Sous-vide intentionally avoids exactly those conditions.

Temperature Alone Tells Only Part of the Story

It’s tempting to assume that if a sous-vide bath is set to a high temperature and run for many hours, the effect would be similar to boiling. But this overlooks two important differences.

First, water temperature in sous-vide is capped by design. Even at the upper end, it remains well below the effective temperatures reached inside a pressure cooker, where boiling points rise dramatically under pressure.

Second, sous-vide food is sealed off from direct water interaction. This matters more than it sounds.

When foods like beans or grains are boiled conventionally, lectins can leach into the cooking water. Discarding that water physically removes some lectin content. In sous-vide, nothing leaches out. Everything remains trapped in the bag, including any lectins that survive the heat.

In other words, sous-vide is extremely efficient at preserving whatever is already in the food. That is a benefit for flavor and nutrients, but a drawback when the goal is reducing biologically active compounds that the body may struggle with.

Pressure Is a Game Changer, And Sous-Vide Lacks It

One of the most effective tools for lectin reduction is pressure cooking. Pressure changes the physics of heat. Water boils at a higher temperature, steam penetrates food more aggressively, and molecular structures are exposed to conditions they would never experience in a standard pot or water bath.

Many lectins that tolerate boiling temperatures begin to lose activity under pressure. Their complex folded shapes, essential for binding to carbohydrates, are more likely to deform in ways that matter biologically.

Sous-vide, by contrast, operates at atmospheric pressure. No matter how long food is held in the bath, the thermal ceiling remains the same. Time can compensate for temperature to a point, but for lectins, that point is often lower than people expect.

The Illusion of “Low and Slow” Safety

There is a common belief that “low and slow” cooking is inherently gentler on the body. For many foods and many people, that can be true. But lectins are a notable exception.

Lectins don’t behave like tough connective tissue that softens over time, or starches that gelatinize predictably. Some lectins can remain active after hours of moderate heat exposure. In certain cases, prolonged low-temperature cooking may even make them more available, by softening surrounding plant tissues without denaturing the lectin itself.

This can create a false sense of security. Food tastes tender, digests easily at first glance, and yet still carries lectins capable of interacting with the gut lining or immune system in sensitive individuals.

Vegetables vs. Proteins: A Critical Distinction

Sous-vide is most often celebrated for meat and fish, which generally do not contain lectins of concern. When people encounter problems, it’s usually with plant foods like legumes, grains, nightshades, and certain seeds.

Using sous-vide on animal proteins while relying on other methods for vegetables is one way people unconsciously avoid problems. But when sous-vide is applied broadly, especially to foods like beans, lentils, or lectin-dense vegetables, the limitations become more obvious.

For example, beans that are unsafe when undercooked remain unsafe when cooked sous-vide at temperatures below boiling, regardless of how long they are held there. Time cannot substitute for the specific structural disruption that high heat and pressure provide.

Nutrient Preservation vs. Antinutrient Persistence

One of the selling points of sous-vide is nutrient preservation. Water-soluble vitamins are not lost to cooking water, and oxidation is minimized. But lectins fall into the category of antinutrients, not nutrients. Preserving them is not always desirable.

This highlights an important distinction: A method that preserves nutrients also preserves antinutrients.

Sous-vide does not selectively protect the good and destroy the problematic. It preserves what is there. For individuals who are lectin-sensitive or experimenting with a low-lectin lifestyle, this can slow progress or create confusing results.

People may assume they are “doing everything right” because they are cooking carefully and avoiding raw foods, yet symptoms persist. The issue isn’t effort. It’s mismatch between method and goal.

Why This Matters for Digestive and Immune Sensitivity

Lectin sensitivity is not uniform. Some people tolerate lectin-containing foods with little issue. Others experience digestive discomfort, joint pain, skin reactions, or neurological symptoms that improve when lectin exposure is reduced.

For those in the second group, cooking method matters profoundly. Sous-vide’s strengths like precision, consistency, and preservation, do not align with the biological challenge lectins present.

This does not mean sous-vide has no place in a low-lectin kitchen. It means it should be used strategically, not universally. Animal proteins, certain low-lectin vegetables, and post-processing steps can all benefit from sous-vide. But relying on it as a primary lectin-reduction tool is likely to disappoint.

A Tool, Not a Solution

Sous-vide is neither good nor bad in isolation. It is simply optimized for a different goal. When the objective is tenderness, moisture retention, and flavor control, it excels. When the objective is disrupting resilient plant defense proteins, it falls short.

Understanding this helps remove confusion and frustration. It explains why someone can eat beautifully cooked, carefully prepared food and still feel “off.” It also underscores a larger point that runs throughout modern lectin research: how food is prepared can matter as much as what food is chosen.

In a low-lectin approach, success often comes not from adopting the newest cooking trend, but from matching the method to the biology. Sous-vide shines in many areas, just not in lectin reduction.