For years, lectins have stirred debate in nutrition circles. Some people swear that reducing lectins transformed their digestion, inflammation levels, and energy. Others barely notice a difference. What’s behind this inconsistency? Why do certain lectin-rich foods trigger noticeable symptoms while others slide through the system without much drama?

This is where understanding how lectins behave in the body and how different foods package those lectins becomes incredibly helpful. High-lectin foods vary widely in structure, potency, and how we prepare them, making some far more problematic than others.

This guide breaks down the science in plain language: what lectins are, why some lectins are harsher on digestion than others, which foods contain the highest amounts, and how proper preparation can drastically reduce their effects. Whether you’re exploring a low-lectin lifestyle or simply curious about these plant proteins, this article offers a grounded look at what really matters.

What Are Lectins, Really?

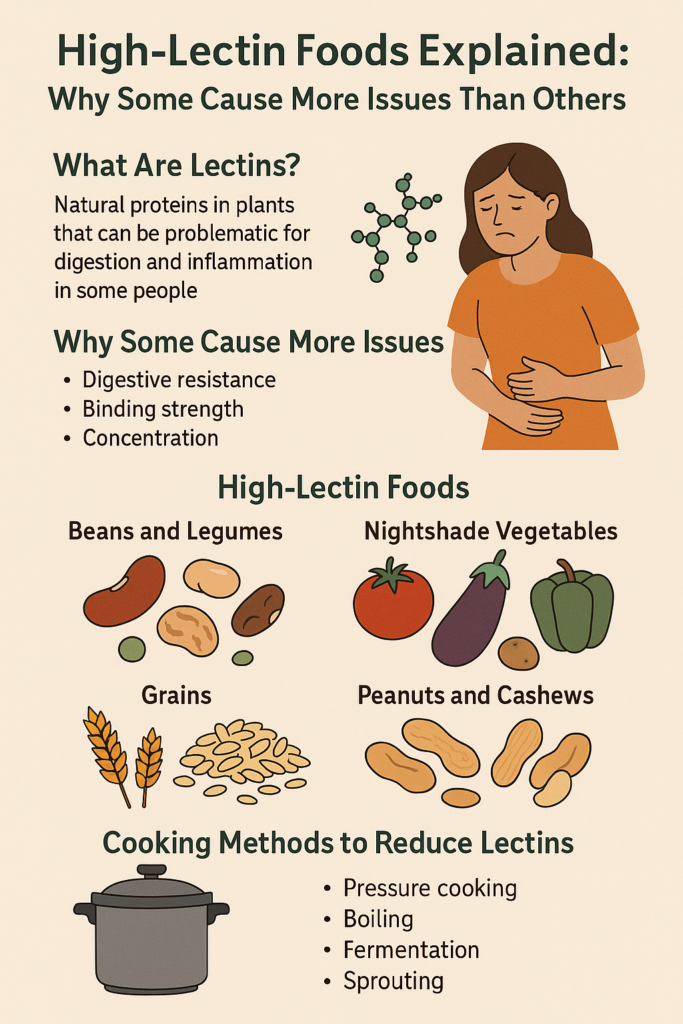

Lectins are naturally occurring proteins found in plants, created as part of the plant’s built-in defense system. Unlike animals, plants cannot run away or protect themselves physically, so they rely on biochemical tools like bitterness, toxins, and compounds like lectins to discourage predators from eating them.

A key feature of lectins is their ability to bind to carbohydrates. This might sound harmless, but inside the human digestive system carbohydrate-binding proteins can interact with gut cells in ways that affect permeability, digestion, and immune signaling.

Some lectins pass through the body without much interaction at all. Others may resist digestion, cling to intestinal walls, or trigger immune responses in sensitive individuals. This is why lectins vary so dramatically in their effects.

Why Some Lectins Cause More Problems Than Others

Not all lectins behave the same. Their strength, structure, and how tightly they bind to intestinal cells determine how irritating they may be. Here are the major factors that influence a lectin’s “trouble-making potential”:

1. Digestive Resistance – Many proteins break down easily during cooking or digestion, but not all lectins. Some, especially those found in beans and legumes, are remarkably tough. If they aren’t neutralized through proper cooking or pressure cooking, they can survive long enough to interact with your gut lining.

2. Binding Strength – Different lectins bind to different carbohydrate structures. Some bind weakly and pass through the body without much friction. Others bind tightly to intestinal cell surfaces, potentially interfering with nutrient absorption or contributing to digestive discomfort.

3. Concentration – Some foods contain only small traces of lectins. Others, like kidney beans and wheat germ, contain much higher concentrations. High-dose exposure increases the likelihood of noticeable symptoms.

4. Preparation Method – Raw or improperly cooked lectin-rich foods can cause significant issues. But when cooked correctly like being soaked, sprouted, fermented, or pressure cooked, the lectin activity in many foods drops dramatically. The difference between “safe” and “problematic” often comes down to technique, not the food itself.

5. Individual Sensitivity – Not everyone responds the same way. Some people have robust digestive systems and tight gut barrier function. Others may deal with:

- dysbiosis

- autoimmune tendencies

- chronic inflammation

- previous gut irritation

…all of which make lectin exposure more noticeable.

Understanding these distinctions helps explain why foods from the same category like beans, nightshades, and grains, can vary so widely in their effects.

High-Lectin Foods and Why They Matter

Below is a breakdown of major food groups known for containing higher levels of potentially problematic lectins. The focus here is not fear-based; it’s about clarity and understanding. Many people eat these foods with no issue, but sensitive individuals may find significant relief by modifying or reducing them.

1. Beans and Legumes: The Most Potent Lectin Source

Why They Can Be Problematic

Beans are seeds, and seeds are nature’s most heavily protected plant parts. Lectins in legumes such as kidney beans, soybeans, black beans, and lentils are designed to resist digestion and discourage predators.

Raw kidney beans, for example, contain a particularly strong lectin called phytohemagglutinin. Consuming just a small amount of undercooked kidney beans can cause severe digestive distress like nausea, vomiting, cramping, and diarrhea that sometimes is mistaken for food poisoning.

The Good News

When properly prepared; soaked thoroughly, boiled vigorously, or pressure cooked, lectin levels drop dramatically. Traditional cuisines around the world learned this long ago, which is why improperly cooked beans are rare in traditional recipes.

Still a Concern For Some

Even well-cooked legumes may cause symptoms in sensitive individuals, especially those dealing with inflammatory or autoimmune conditions. For them, limiting beans or relying only on pressure-cooked varieties can bring major improvements.

2. Nightshade Vegetables: Seeds and Skins Carry the Punch

Nightshades include tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, and peppers. While these foods are lower in lectins than beans or grains, the lectins they contain are concentrated in the seeds and skins.

Potential Issues

Nightshade lectins can be irritating for two main reasons:

- They bind to gut cell receptors more readily than some other lectins.

- They are often eaten raw, especially peppers and tomatoes, increasing exposure.

For individuals with digestive sensitivity, autoimmune conditions, joint pain, or chronic inflammation, these lectins may contribute to flare-ups.

Simple Fixes

- Peel the skins

- Deseed the tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers

- Pressure cook tomato sauces to reduce lectin activity

Many people find they can tolerate nightshades again once prepared this way.

3. Grains: Wheat, Barley, Rye, and Beyond

The Lectin to Watch: Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA)

WGA is found in the outer portion of the wheat kernel (the germ), and unlike gluten, it is not broken down by heat, fermentation, or stomach acid.

WGA has a strong affinity for the gut lining. Even small exposures can cause symptoms for people who are lectin-sensitive or dealing with intestinal permeability.

Grains That Also Contain Lectins

- Barley

- Rye

- Oats (particularly non-gluten-free oats that may still contain lectin-active bran)

- Quinoa (a seed but often grouped with grains)

Why Some People React Strongly

Grain lectins are eaten frequently, often multiple times a day, making chronic exposure more likely.

4. Peanuts and Cashews: The Sleeper Lectin Sources

Although most nuts are lower in lectins, peanuts and cashews behave differently because they are not true nuts. Both are legumes or legume-adjacent species.

Why They Can Be Problematic

- They contain lectins similar to those in beans.

- Cashews contain compounds related to poison ivy family plants, which can also cause reactions in some individuals.

- Peanuts often harbor mold residues that add another layer of digestive stress.

For people transitioning to a low-lectin lifestyle, these foods are often among the first removed.

5. Certain Seeds and Seed-Based Products

Seeds are heavily protected plant structures, so some seeds contain lectins that discourage digestion. Chia seeds, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, and sesame seeds are generally better tolerated, but sensitivity varies widely.

Problem Seed Products

- Seed-based oils

- Raw seed flours

- Seed pastes (like tahini or sunflower butter)

Roasting and fermenting can reduce lectin activity, but very sensitive individuals may still experience symptoms.

How Do Lectins Affect Digestion and Inflammation?

Once lectins reach the digestive system, several things may happen depending on which lectin is involved and how sensitive a person is.

1. They May Bind to Gut Lining Cells – This can disrupt normal cell signaling and interfere with nutrient absorption.

2. They May Contribute to Increased Gut Permeability – Often described as “loosening the gut junctions,” certain lectins can irritate the gut lining, making it easier for particles to pass through. This does not happen to everyone, but in those predisposed, lectins may play a role.

3. They May Interact With the Immune System – When lectins bind to immune-active parts of the intestine, they may trigger inflammation in response.

This is why individuals with autoimmune diseases, IBS, or gut dysbiosis often report significant symptom relief when reducing lectins.

Cooking Methods That Dramatically Reduce Lectin Activity

One of the most important things to understand is that lectins are not universally harmful and in many cases, they are easy to neutralize.

Best Methods (Most Effective to Least)

1. Pressure Cooking

The gold standard for neutralizing lectins.

Perfect for:

- Beans

- Lentils

- Potatoes

- Tomato sauces

This method reaches high temperatures that standard boiling cannot, making it the most reliable lectin-reduction technique.

2. Boiling (Rapid Boil, Not Slow Cooker)

A vigorous boil for an extended period can substantially lower lectin activity.

Important: Slow cookers do not reach high enough heat to destroy lectins in beans or legumes.

3. Fermentation

Microbial action can break down lectins naturally.

Great for:

- Soy (tempeh, miso)

- Vegetables

- Grains if fermented traditionally

4. Sprouting

Can reduce lectins in seeds and legumes but not nearly as effectively as pressure cooking.

5. Peeling and Deseeding

Excellent for nightshades:

- Tomatoes

- Peppers

- Cucumbers

The bulk of lectins live in the skin and seeds.

Why Reactions Vary So Much Between People

Some individuals thrive on legumes and whole grains. Others struggle. Here are the main reasons for this disparity:

1. Differences in Gut Barrier Strength – A healthy gut barrier prevents most lectins from interacting with the immune system. When permeability increases, lectins may have more influence.

2. Variations in Microbiome Composition – Some gut bacteria break down lectins naturally. If your microbiome lacks these strains, lectins may be more irritating.

3. Enzyme and Digestive Variations – Digestive enzyme activity varies by person. Those with lower enzyme output or reduced stomach acid may find lectins harder to break down.

4. Autoimmune Predisposition – People with autoimmune tendencies often report significant symptom improvement when lowering lectins.

5. Frequency of Exposure – Daily exposure through beans, grains, seed oils, and nightshades compounds the effect.

Should You Avoid High-Lectin Foods Completely?

Not necessarily. A low-lectin lifestyle isn’t about fear. It’s about strategy.

Most people do well with:

- Proper preparation

- Moderation

- Variation in diet

Those with significant digestive or inflammatory conditions may benefit from stricter avoidance initially, then gradual reintroduction to test tolerance. Many people find that after healing their gut, they can reintroduce certain foods (especially peeled, deseeded, and pressure-cooked versions) without symptoms.

Final Thoughts

High-lectin foods don’t impact everyone equally but for those who are sensitive, understanding how different lectins work can be life-changing. The key is not to villainize entire food groups, but to learn how to prepare them correctly and pay attention to your own body’s signals.

By focusing on proper cooking, strategic food choices, and an informed approach to lectin-rich foods, individuals can reduce discomfort, support gut health, and personalize their nutrition in a meaningful way. Whether the goal is better digestion, reduced inflammation, or simply clarity about how your body responds to certain foods, learning the “why” behind lectin variability gives you the tools to make confident, supportive decisions.